Elevate your design and manufacturing processes with Autodesk Fusion

Many hotter parts of the world have plenty of humidity, but limited infrastructure for delivering clean water to citizens and businesses. Vena Water is working to address that scarcity with a highly efficient atmospheric water generation (AWG) system that draws water from the air using solar and geothermal energy.

Humidity + Sunlight = Clean Water

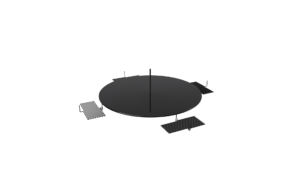

Vena’s system cleverly takes advantage of basic atmospheric science to collect water. The unit consists of a broad disk at ground level, with a thermal tower reaching up into the air from the center of it and a condensing well penetrating the earth beneath it.

Sunlight heats the air inside the unit. Because heat rises, that air passes up through the thermal tower, drawing cooler ambient air into the unit behind it. That ambient air is channeled into the subterranean part of the system, where the cooler earth surrounding the unit lowers the temperature further. (It works much like a heat-pump air-conditioning system.) At that stage, the cooled air is supersaturated with moisture — like fog.

In the condensing chamber at the bottom of the system, Vena’s specialized technology causes the moisture in the air to condense into liquid. Dry air leaves the system through the thermal tower, while the liquid water is pumped to the surface to be purified.

The Need for Clean Water Delivered Off-Grid

Many of the regions that Vena is targeting need “a decentralized and off-grid approach to resource management,” according to John Walsh, Vena’s co-founder and CEO. That need arises not only because of the difficulties of accessing and delivering the water itself, but also because of the high energy costs connected with doing so.

Any AWG system can potentially address that need by delivering clean water without tapping existing infrastructures. Unfortunately, traditional AWG technologies have some serious drawbacks, including low energy efficiency and high maintenance costs.

Some companies have put up with those drawbacks for lack of any better choice. In regions like India, the big users of AWG have been industrial facilities such as bottling plants. But according to Walsh, the answer is “to get these facilities that have unsustainable water practices off of these precious groundwater sources.” That’s exactly what Vena is aiming to do with its innovative AWG system, which runs on half as much energy as traditional technologies — 0.2 kWh per liter instead of 0.42 kWh per liter.

Broadening the Reach of AWG

The company, which has teams in Los Angeles, San Diego, and Brooklyn, initially focused on delivering an AWG solution that could be delivered to a remote location in a shipping container for temporary use during relief efforts.

But as Thomas Kosbau, Vena’s other co-founder and CTO, puts it, “If we’re making water for people, the relief market is small.” Likewise, he says, “[our] original design was very limited” — able to produce only 100 liters of water per day.

Vena wanted to have a bigger impact on water scarcity, which is why they pivoted to a new design that yields a much higher volume of water — thousands to tens of thousands of gallons per day. The new model is useful not only for aid situations, but also for applications in agriculture, industry, and municipal or regional infrastructure. As Walsh explains, this gives Vena the chance to have a much larger impact to address water scarcity as a whole.

Building a Company around a Great Idea

Walsh got interested in the problem of water scarcity and the possibilities of AWG while running GrowEnergy, a company he had founded to generate energy from algae. At GrowEnergy, he had worked with Kosbau, Tim Perry (now Vena’s project engineer), and Zac Fowler (Vena’s systems engineer).

As they turned their attention to the challenges of AWG, Kosbau’s design company, ORE developed the 1.0 version of Vena’s product. As the project gained momentum, Walsh formed Vena Water in early 2014.

Kosbau laughs when he relates the next step in their journey: “We brought some engineers into the company, and, lo and behold, we got a much better machine.” The new design opened their eyes to AWG’s applications beyond the aid sector.

The company was seeded with $300,000 from grants, family friends, and bootstrap investments from Walsh and Kosbau. Since then, it has also received funding and other types of support from the LACleanTech incubator, design competitions, and the Autodesk Entrepreneur Impact Program.

The Power of Rapid Iterative Design

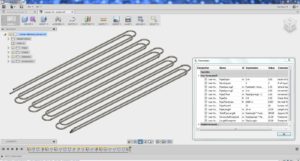

According to Perry, “Each of those pivots [in design] really meant starting from scratch in the CAD.” Today, the Vena Team uses Fusion 360 to experiment with different configurations of existing components and with scaling. Using the software helps them with “making sure we’re all on the same page and th inking about the same things.”

inking about the same things.”

Perry adds that it was often difficult to put design ideas into words during meetings, but once the team had 3D models to look at together, “we became much more productive.”

Kosbau finds Fusion 360 especially valuable because it’s cloud-based and collaborative, which is important for Vena’s geographically dispersed team. The software has enabled them to “make a lot of iterations quickly and prove assumptions — or disprove assumptions” before creating a physical model.

The CTO is now getting the entire team fully trained on Fusion 360 so they can get even more out of it, and he’s especially excited about using it with computational flow dynamics (CFD): “We think that’s going to be the next level [for our design].”

Bringing Durable, Inexpensive New AWG Technology to the Real World

Walsh says he’s grateful for what the software does for Vena, and excited about the specific advantages of the design they’ve created. Besides having dramatically lower energy costs, the Vena system is also a much more permanent solution because it’s installed in the ground. The team is extending that advantage by ensuring that all of the system’s parts either have a long lifespan or are easy and cheap to replace.

Walsh says he’s grateful for what the software does for Vena, and excited about the specific advantages of the design they’ve created. Besides having dramatically lower energy costs, the Vena system is also a much more permanent solution because it’s installed in the ground. The team is extending that advantage by ensuring that all of the system’s parts either have a long lifespan or are easy and cheap to replace.

Right now, the Vena team is a constructing a 100-gallon-per-day prototype for testing in La Jolla, California. Kosbau is sure that the team will learn all kinds of things they didn’t know they would once they have a real-world model up and running.

He’s eager for that testing and learning: “It’s very exciting to get it plugged into the ground and pulling water out of the air.”