People often use the terms “recycled water” and “reclaimed water” interchangeably. The most inclusive definition of both together would be any water that has been captured after use and then treated and reused, rather than sent directly into natural drainages.

This definition covers everything from reused irrigation water to highly treated, re-purified water that is sent through commercial and residential water faucets for drinking. But it doesn’t give us deeper knowledge of the two categories. Nor does it help us recognize how water is reused in our surroundings and communities. So, let’s take the plunge into the different ways water is reused.

How do we use all of this recycled water? The answer really depends on whether the water is potable or non-potable – drinkable or not.

Potable = safe to drink

Potable recycled water is wastewater that has been purified to meet all government standards for safety and health and is safe to consume. Usually, recycled potable water is delivered back to water customers in several ways, such as in drinking water systems.

Indirect potable reuse (IPR), sometimes called de facto or unplanned potable reuse, means that treated wastewater is pushed back into the larger water supply, usually a river, lake, reservoir, or groundwater. This water is then eventually reused, either by the same community or an adjacent one, sometimes as drinking water. While the water rests in the larger water supply, it can serve a positive purpose: California’s Orange County Groundwater Replenishment System uses IPR water to act as a seawater intrusion barrier and for recharging groundwater basins.

Unplanned potable reuse becomes planned reuse when the water is finally refined and accompanied by processes for compliance and public accountability. Most U.S. states have regulations or guidelines for water reuse, and these regulations are updated and developed as needed once states gain experience and confidence in water reuse. Most states will also consider potable reuse projects on a case-by-case basis.

Direct potable reuse (DPR) sends treated wastewater directly into a potable water supply distribution system, either just upstream of a water treatment plant or within the plant itself. These are projects that inspire media reports of “toilet-to-tap” water, a term that can make people … uncomfortable. But DPR is not as icky as it sounds, as we’ll show you just a bit later.

Non-potable = not drinkable, but still usable

Non-potable recycled water is reclaimed water that is not used for drinking. Instead, it is made safe for irrigation, industrial uses, or other non-drinking water purposes. Major water consumers in agriculture and industry have been using such water for decades in processes like cooling; for example, inside air-conditioning systems or nuclear power plants. While these systems involve enormous amounts of water – and offer opportunities to support local environments and water systems – they often operate outside public drinking water systems.

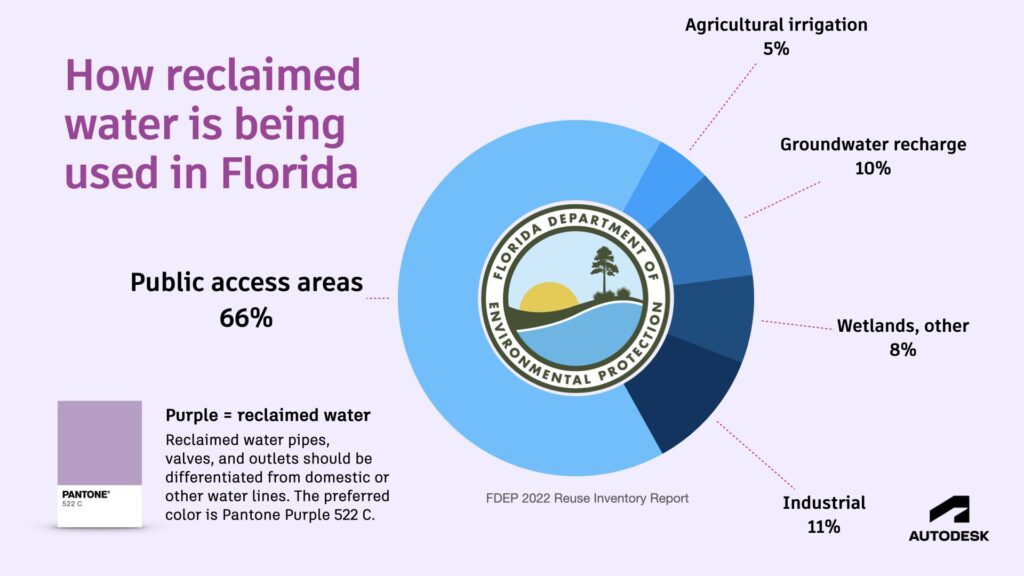

Believe it or not, Florida actually leads in Public Access Reuse (PAR) of water in the United States, utilizing an average of 908 million gallons of reclaimed water every day.

A few smart uses for reclaimed wastewater include:

- Public park irrigation

- Street cleaning

- Fire protection systems

- Vehicle washing

- Dust control

- Aquifer recharge

- Wildlife habitats

Why is recycled water increasingly important?

Even though Flint, Michigan and Jackson, Mississippi have suffered long-term water crises, for the most part, safe, readily available water is something we have tended to take for granted in the United States. But in other places around the world, especially in desert nations, water supplies can be unreliable or dangerous to health. Climate change and associated drought are reducing water levels and driving up costs everywhere, including in Europe and North America. This naturally makes water recycling increasingly important for maintaining water supply.

Are we really planning to drink “toilet-to-tap” water?

If current climate-change-related shifts continue, yes. Toilet-to-tap water may be coming soon to a utility near you, ick factor and all. In truth, this treated sewage water is effectively indistinguishable from other treated water, and your local utility may already be adding it into your water supply.

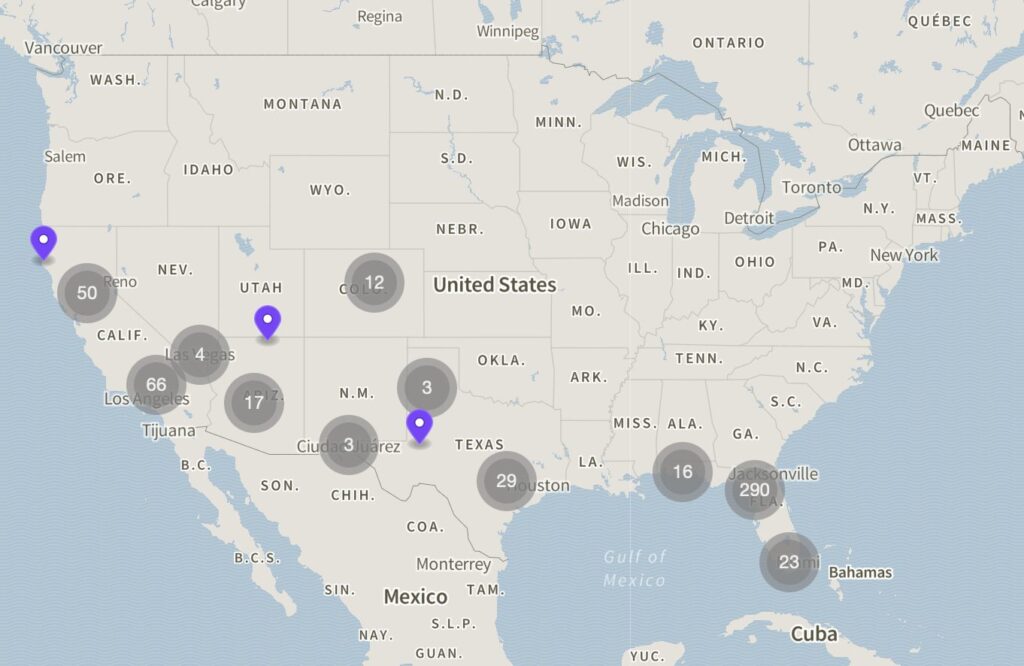

DPR water is legal in Texas, and legal in some cases in Arizona. Many other states are considering legalizing use of the potable former-sewage water, including California, and Colorado. The Reclaimed Wastewater Map, created by the U.S. Federal Energy Management Program, shows where this water is in use.

Does your local water provider use reclaimed water? The Department of Energy’s Reclaimed Wastewater Map shows all water utilities in the US that produce reclaimed wastewater and sell it back to their customers.

In Sweden, a brewery is using DPR water to make beer, as is Singapore’s water agency in its efforts to promote awareness of water scarcity issues. And, hey! Astronauts drink recycled water all the time because water is at a premium while onboard a space station. That recycled water includes humidity and, yes folks, urine.

How does water recycling work?

Water purification uses a wide variety of technologies and processes. For example, the water for that Swedish beer is first filtered through a combination of conventional microbiological treatment and an ultrafiltration membrane. Second, the water goes through a very tight reverse-osmosis membrane, which removes almost 100% of all chemical substances. An activated carbon filter removes harmful organic substances, and, finally, ultraviolet light kills any remaining bacteria. The result is considered fully purified water that’s safe to drink.

More ways we talk about recycling water

Gray water is water segregated from a domestic wastewater collection system and reused on site. This usually means sources such as showers, bathtubs, sinks, and washing machines — but not toilets. While gray water usually contains some soaps and detergents, it’s still suitable for non-potable use. Many buildings and homes have their own systems for capturing, treating, and distributing gray water for irrigation or other non-potable uses. These systems and their gray water play an important role in addressing water conservation goals.

Standards and rules about the use of gray water vary from state to state, with some states like California boosting the installation of gray water systems by offering cash incentives to homeowners. The state’s Santa Clara Valley Water District offers rebates to homeowners who install a graywater “Laundry-to-Landscape” system that sends clothes washer rinse water directly to gardens and backyards.

Black water is a mixture of water with excrement or urine. Black water flows into waste water systems after you flush the toilet.

Purified water has passed through treatment processes and has been verified as safe for augmenting drinking water supplies.

Raw water is untreated surface or groundwater.

Wastewater is used water from a community or industry that contains dissolved and suspended matter in addition to organic waste.

Sewage is wastewater from households and businesses that contains organic waste.

Industrial/commercial wastewater is liquid waste generated by industries, small businesses, and commercial enterprises. Businesses are usually permitted to dispose of this wastewater in drains, thus adding it to the general supply. Often, this water undergoes some onsite treatment.

No matter what you call it – reclaimed water, recycled water, gray water, or DPR water — it’s all water. And it’s likely that your community will be using and reusing this water in the future, in one way or another, to help conserve this vital resource.