What do Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Machiavelli, Raphael, Galileo, Brunelleschi, and Botticelli all have in common? They all, at one point, lived in Florence, Italy. Home to the powerful and beneficent Medici family, this Renaissance city located beside Tuscany’s longest river, the Arno, has long been a wellspring of art and culture. But it’s also been a wellspring of too much water.

The flood of the Arno

You can find inscriptions on the walls of Florence that show flood levels from 1177, 1333, 1547, 1557, 1740, and 1844, but the worst flooding occurred in 1966, when up to 200 mm of rain fell on the watershed of the Arno river within 24 hours – one quarter of the region’s annual rainfall. With no warning system in place, 600,000 tonnes of mud, rubble, and sewage mixed with heating oil inundated the city, claiming over 100 lives, leaving 20,000 homeless, and ruining countless artefacts.

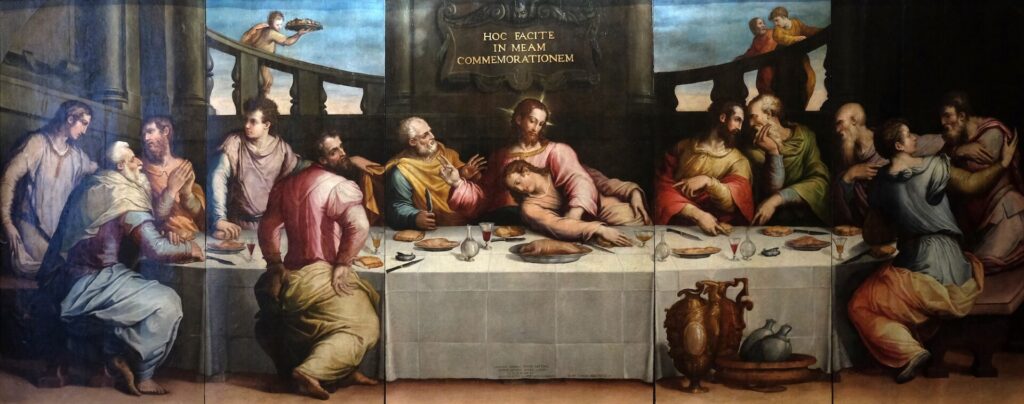

Perhaps the worst flooding was in Florence’s most historic neighbourhood, Santa Croce, which is filled to the brim with art and culture inside medieval-era buildings. Giorgio Vasari’s Last Supper, located in the Opera di Santa Croce, ended up underwater, along with over 1 million historic books and records in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, the national library.

The eternal battle against forgetting the past

The world came together to repair the damage. Florence native Franco Zeffirelli immediately dropped filming of Taming of the Shrew with Elizabeth Taylor to make a film about it with Richard Burton narrating in Italian, which reputedly raised $20M to help with rebuilding. But as the event drifted into the past, it seemed harder and harder to muster the community to action.

Multiple plans were proposed to address the situation over the next 50 years, and many books were written about the flood, which are collected at the CEDAF flood documentation center, making the flood of the Arno perhaps one of the most well-documented floods ever. But as with so many flood dangers, over time it becomes easier and easier to forget about preparing for the next flood.

But hydraulic modeler Paolo Tamagnone didn’t forget.

“Italy holds most of the world’s cultural heritage, but it has a territory widely subject to high hydrogeological risk,” says Tamagnone. “While most research on flood risk focuses on potential monetary losses, those costs would be exponentially higher if we took a more holistic view and calculated the losses in cultural heritage.”

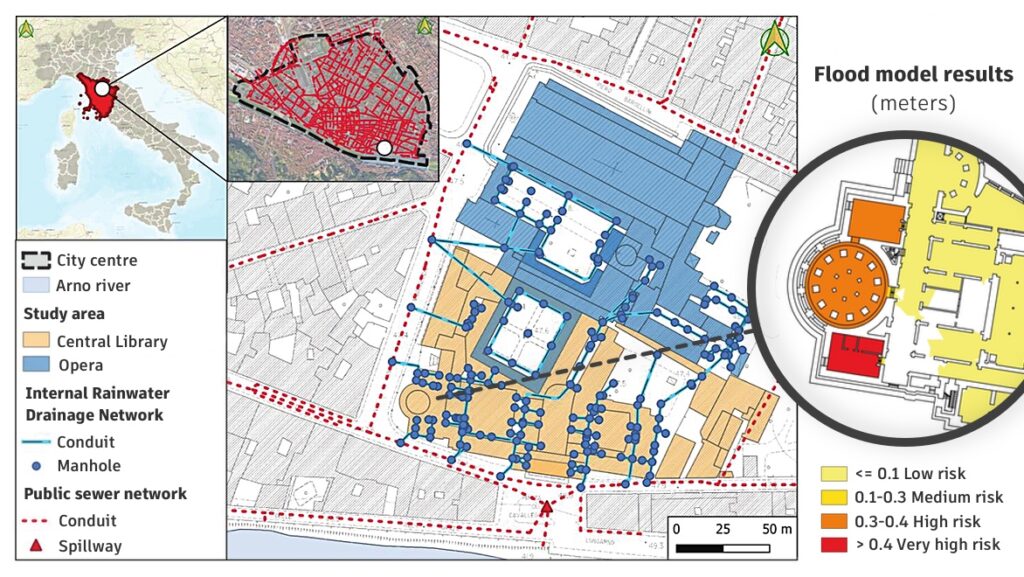

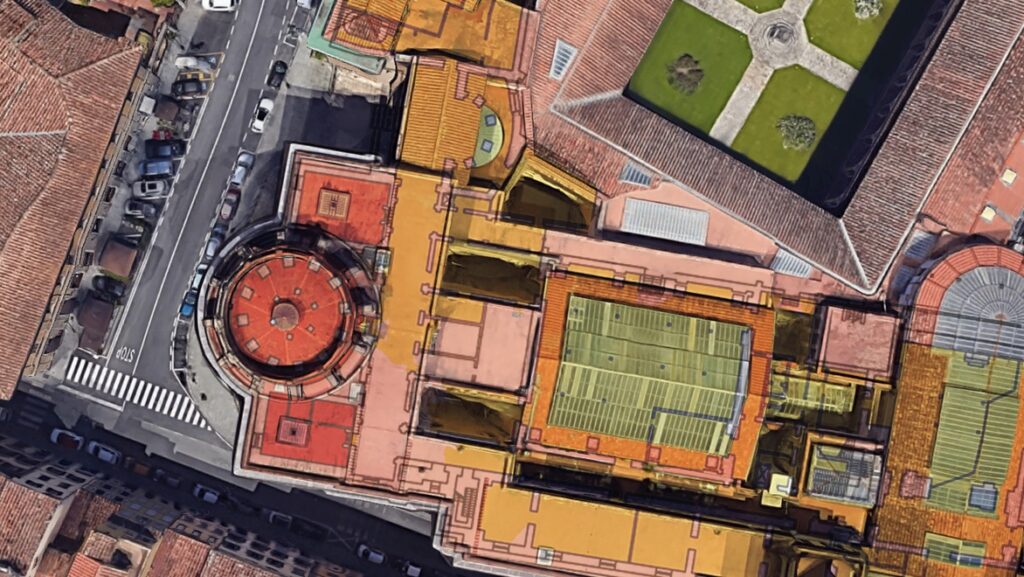

As a post-doc candidate at Università degli Studi di Firenze, he saw an opportunity to apply the skills in his area of study of hydraulic modeling to help protect the cultural heritage of the city centre from pluvial flooding. He proposed an extensive project to map the area, in particular two areas he considered especially vulnerable, the monument complex and the library.

Modeling the full flood with multiple scenarios

The Arno river flows from the Mount Falterona hills of the Apennine Mountains through Florence and eventually to the Ligurian Sea. Modeling the overland runoff that flows from the Apennine mountains to the upper basin to the Arno is straightforward enough. But predicting pluvial floods further down the line becomes more complicated when there are countless interactions that need to be captured between all of the hydraulic phenomena happening in the city’s sewer system.

So, while the most obvious risk of flooding may come from close proximity to the river, it’s the pluvial flooding from the mountains that compound the problem. Perhaps the biggest challenge for Tamagnone was assessing what would happen inside the Internal Rainwater Drainage Network’s (IRDN) catacombs when the river is full.

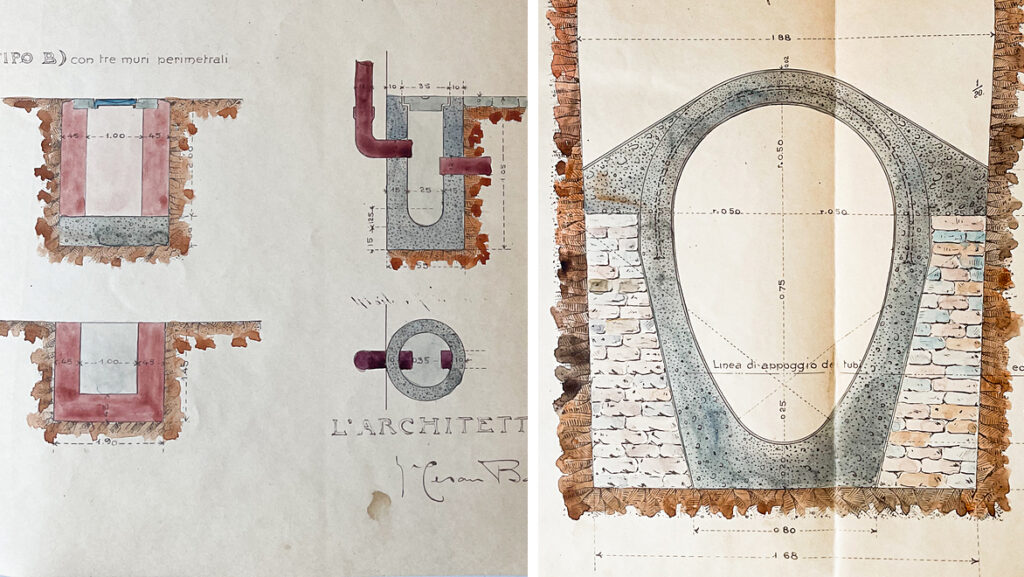

Because the IRDN is directly linked to one of the main sewer conduits of the city, the Chiesi sewer pipe – named after its 19th-century engineer designer, Flaminio Chiesi – the effects of pressure in this unique warren of pipes can be hard to predict.

Tamagnone turned to Autodesk partner HR Wallingford because he believed InfoWorks ICM could be used to evaluate both 1D and 2D interactions between surface runoff processes, the urban sewer system, and the internal drainage network, provided he could model the many buildings and sewer networks in the IRDN area to 100% accuracy. “I chose InfoWorks ICM because I needed to create a detailed hydraulic model that was able to contemplate both what happens on the surface and underground with the propagation of flow through the pipes.”

Merging data from multiple sources

He was fortunate to be able to begin his work by retrieving existing models of the public sewer network (PSN) directly from the regional public utility, Publiacqua, who are also supported by Autodesk partner HR Wallingford. This was made even easier by the fact that these water professionals also use InfoWorks ICM. He was able to seamlessly nest his hydraulic models into theirs and take advantage of all the data collected in those models.

Next up was reconstructing the IRDN of the historic buildings to identify all connections to the urban sewer network. Although the city of Florence’s digital terrain model of the area included information about the external areas surrounding the key buildings – the yards and cloisters – the insides of these buildings needed special forensic treatment. So he started digging deeper with his research.

Making the medieval digital

In addition to surveying and measuring the buildings by hand, Tamagnone was able to mine multiple historical archives, including the CEDAF flood documentation center, to find original blueprints. Many of the technical drawings of these medieval-era buildings are over one hundred years old, but they contained information that helped him reproduce and geolocalize the geometrical specifications of the IRDN, all the way down to manhole specifications and altimetry of the floors.

“The elevation is maybe the most important variable when we speak about pipes and flow movement,” says Tamagnone. With all this data assembled and digitised, he was able to accurately simulate the full range of elevation in the area and how water would flow.

Modeling the extremes

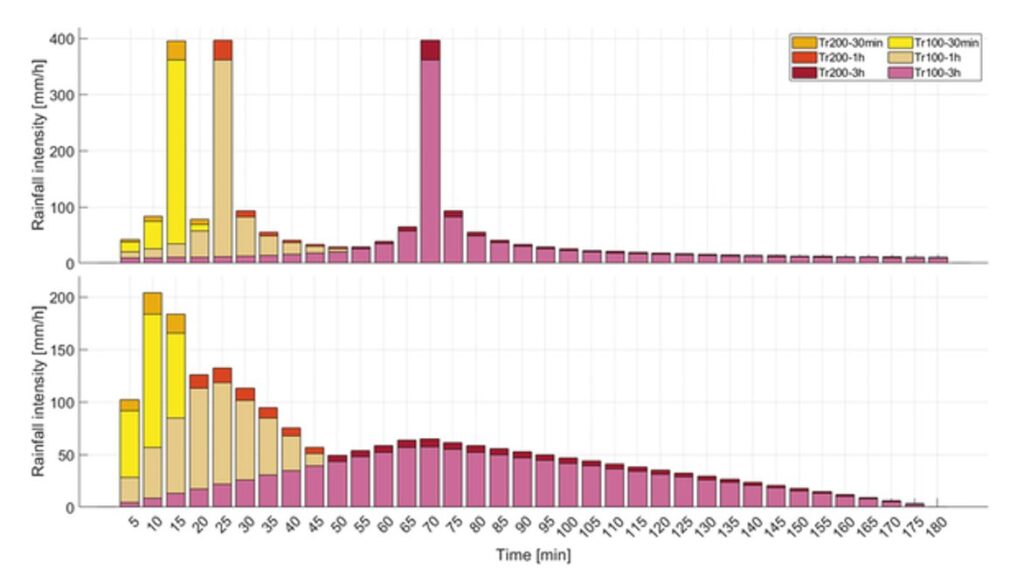

For his flood hazard assessment, Paolo used InfoWorks ICM to create a 1D/2D dual-drainage model that simulates all hydraulic phenomena occurring within the sewer network, as well as flood propagation within the IRDN. He created two basic types of scenarios:

- Hydrometeorologic forcing: He chose to represent extreme rainfall events occurring during dry periods, short and high-magnitude rainfall, the kind that typically induce pluvial flooding events. His hyetographs ranged from 30 minutes to 3 hours and from 60 mm/h to 400 mm/h of intensity (Tr 100 and 200 years).

- Spillway-closed: He also modeled scenarios that simulate the concurrence of extreme rainfall events above Florence and high-water levels in the Arno River (similar to the 1966 flood of the Arno) which cuts out the possibility of the public sewer network being able to discharge excess stormwater through the emergency spillways.

Running the model in InfoWorks ICM

By running the models in InfoWorks ICM, he was able to first understand that Flaminio Chiesi had thankfully built big with his original designs. The model showed that IRDN’s conduits were more oversized than expected, almost as big as in the larger city sewer network.

The model showed that they could handle high-intensity rainfall events. The bigger danger came in the wettest scenarios with high-water stages in the public sewer network and closed spillways. This produced a worrisome backwater effect into the IRDN. The worst spot in his models was directly beneath the library, and it predicted the worst type of issue – sewage flowing into the building.

The opera was safe. But the library…

He had good news, too. By simulating so many scenarios, Tamagnone was able to determine that the opera complex would be spared even in the most extreme situations, partly due to its further distance from the public sewer network. Since all of the manholes are located outside, only minor flooding occurs in the courtyards and car parks, without threatening the cultural heritage safeguarded inside of the building.

But the library was most definitely at risk. In his most destructive models, with extreme rainfall events and a high-water stage of the Arno and all overflow spillways closed, the basement could be severely damaged, flooding by up to 40 cm (or even more). To make matters worse, the underground floor happened to be an area designated for books and ancient newspaper collections, which are vulnerable to humidity from even small infiltrations of water.

Prevention and mitigation strategies

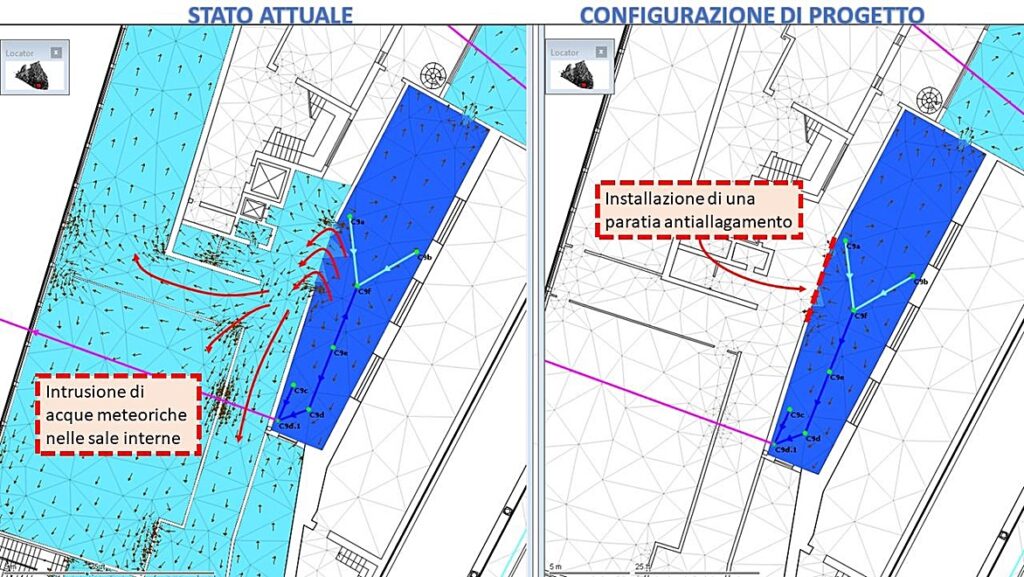

With all this information in hand, he was able to propose a two-pronged strategy as part of a documented emergency plan. First, he proposed a structural strategy of building an anti-flooding barrier to prevent stormwater intrusion, which uses the results from his model to determine the recommended height of the barrier.

In addition, he proposed a non-structural strategy of creating flood risk maps for the staff and administrators to highlight the most exposed and at-risk areas. With this information, the library’s staff now have the knowledge they need as part of their emergency response plan to move especially vulnerable collections to higher ground or seal archival works in a special type of waterproof material with an oxygen barrier.

Preparing for an uncertain climate future

The past 50 years has seen several proposals to prepare Florence for the next flood, but they sometimes fizzle into inaction. Thanks to his meticulous work, Tamagnone has provided not just an extensive InfoWorks ICM hydraulic map and model of the entire historic area, but a process blueprint for others to follow to ensure that their nation’s cultural treasures are safe and protected from flooding.

The library has its own flood documentation collection, which you can visit when you make a pilgrimage to the opera complex to see Giorgio Vasari’s Last Supper from 1546, which was finally restored to an even better condition in 2013, and which now is installed on a winch so it can be raised if necessary. Despite the many challenges the 1966 flood of the Arno presented to Florence, it also birthed new techniques in restoration and conservation, which is another great example of how we can rise to the challenge when the flood comes.

But, of course, it’s always better to be prepared.

Go deeper into the story

The disaster prompted a flood of volunteers who travelled from around Europe to assist. Read about these Mud Angels and how Florence embraced their help.

Many thanks to Paolo Tamagnone and Project TALETE (Tutela del pAtrimonio cuLturale da evEnti esTremi) for providing these hydraulic models, vintage blueprints, risk maps, and courtyard photos. We’re including Paolo’s paper, which has even more technical details and insights that others can use to plan their own flood modeling.