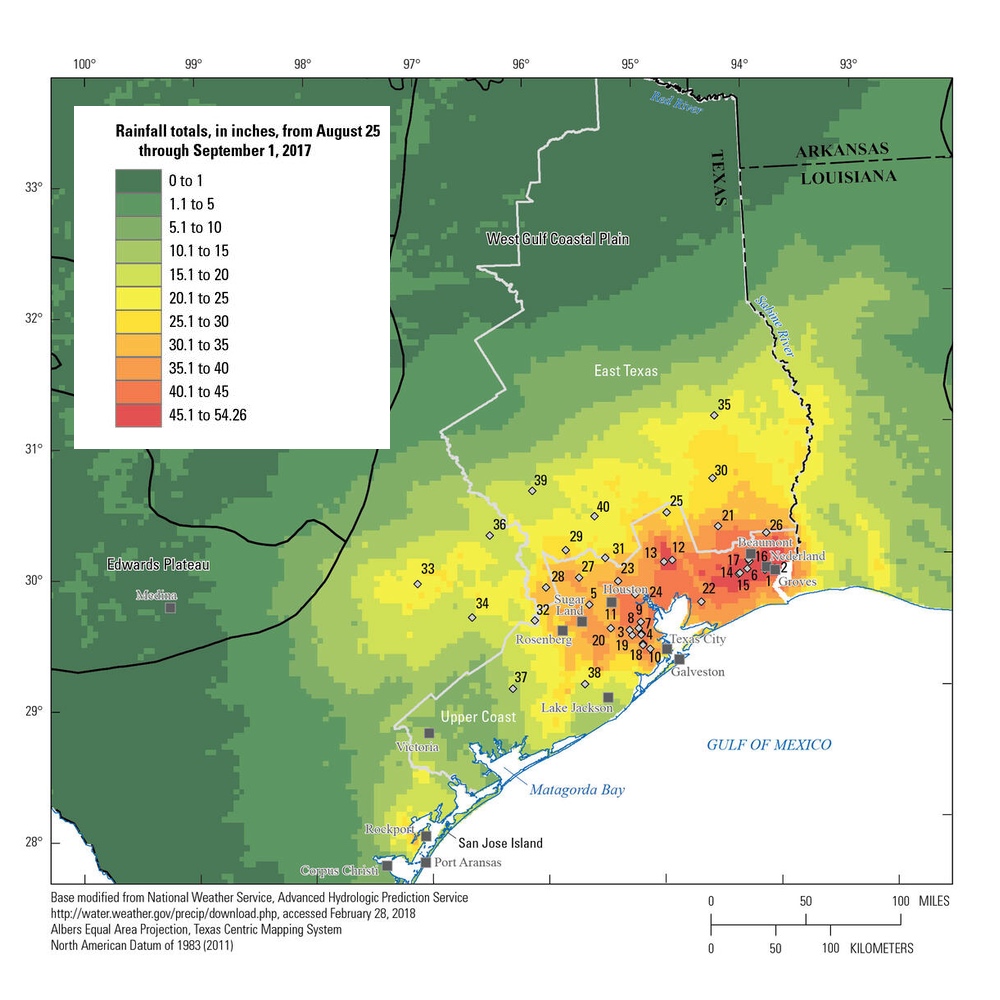

Over eight days in August 2017, category 4 Hurricane Harvey dropped more than 50 inches of rainfall over Houston, Texas, making it the most significant rainfall event in US history since the USGS began keeping records in the 1880s. It resulted in 103 deaths. Just 200 miles away, water professionals and politicians in San Antonio asked themselves: “What if the storm had hit us?” They decided to build a very big InfoWorks ICM model and find out.

In the days leading up to Hurricane Harvey, the San Antonio River Authority (SARA) carefully monitored the work of the National Hurricane Center along with its own flood warning system, relying on the predictive analysis and preparedness plan they had developed in partnership with consulting firm HDR for the City of San Antonio.

They wanted to be prepared in the event the storm’s path led in their direction, which was indeed a possibility. They were on high alert, evaluating multiple anticipated rain events and wind gusts, digging into estimated rainfall data reported by the weather service so the city could have an idea of what to expect. Thankfully, the storm’s path turned and stalled over Houston, never making it to San Antonio.

Disaster diverted… but what if?

One week later, at the Texas Floodplain Management Association’s Fall Technical Summit, as the full extent of the damage across Harris County (the county in which Houston is located) became understood, the hydrologic and hydraulic experts attending couldn’t help asking themselves if San Antonio would have been prepared if the storm had come their way. Someone from the San Antonio City Council explicitly asked a SARA executive if it were possible to model the same impacts of Hurricane Harvey, but with the landscape and unique details of San Antonio. Indeed, they could. Challenge accepted.

Building a comprehensive InfoWorks ICM model

Given just a four-week deadline to provide meaningful results for downtown San Antonio, SARA Project Manager Brandon Hilbrich PE, and HDR Senior Modeler Anthony Henry prepared for the challenge. HDR had already helped SARA develop their flood warning model for the city using InfoWorks ICM, so they had a solid base to begin with. They also had previously conducted a pilot study to help them model the Upper San Antonio River (USAR) watershed in InfoWorks ICM, which includes San Antonio’s downtown and the majority of Interstate 410.

Working with this baseline, HDR added more to their model, importing operational data from ICM Live, steady state HEC-RAS & HEC-HMS model data, as well as XPSWMM 1D/2D data to get the model up to the necessary level of detail for simulating their own super storm. The resulting model was quite thorough, even including existing underground tunnels with pressure flow conduits and operational controls for a dam and two floodgates.

The difference in detail when you model 14 separate storm waves

With the entire physical area modeled to a comprehensive level of detail, SARA then set about piping in water and weather-related data. They included Gauge Adjusted Radar Rainfall (GARR) data from NEXRAD, and each sub-basin parameter was incorporated to develop flow hydrographs. 2D areas were incorporated to allow major storm drain systems to surcharge and capture overland flow characteristics. Due to the significant amount of run-off volume generated by Hurricane Harvey, several 2D areas were added where overland flow volume could transfer between major tributaries and through urban areas.

By utilizing InfoWorks ICM as a complete catchment solution, SARA and HDR had created a holistic model capable of advanced simulations on a single engine, without having to stitch together models from disparate sources. They wanted to push their model to the limit, so they positioned their GARR data directly over the USAR watershed, which provided a truly worst-case scenario assessment for the watershed if the same 50 inches had fallen over San Antonio.

When Hurricane Harvey originally moved through Houston, the GARR data parsed 14 distinct storm waves. In replicating those same weather patterns over San Antonio, SARA discovered that each one of those waves would have been considered a near 100-year storm event. The most intense instance, wave 11, would have lasted for 24 hours and produced 19 inches of rain.

With this level of detail in their model, they were able to determine that the local Olmos Dam would have received 79% of TCEQ 72-hour Probable Maximum Precipitation, would have been overtopped by nearly six feet, and would have spilled onto San Antonio’s Highway 281. Assuming no more rainfall occurred following these 14 storm waves, they found that the highway would have been inundated for 11 days. The dam would have taken 12 days total to empty.

As Hilbrich notes, “The study illustrated the usefulness of the flood warning model in the InfoWorks ICM modeling software and its ability to model not only real-time data, but hypothetical extreme events to provide a better understanding of the city’s preparedness.”

Presenting the results to the San Antonio city council

Having these kind of benchmarks on hand can be incredibly helpful for water professionals who are tasked with protecting a city, not just for storm surge preparation itself, but also when educating and making the case for better preparation to politicians, business leaders, and everyday citizens. Presenting their modelling results to the city council, Graham was able to clearly articulate and illustrate how this particular kind of flooding comes in pulses. “The danger is being caught out in the middle of a storm,” she explained. The flooding would come in pulses, according to the simulation, with the most intense pulse unfolding over around six to seven hours.

But she was also able to relay good news about San Antonio’s fate in such a scenario. Houston is as flat as a pancake, which resulted in vast lakes forming in low-lying areas of the greater Harris County area. San Antonio’s more varied elevation, now mapped comprehensively thanks to the many technologies they employed, means earlier storm waves can rush into gulleys and canyons and find egress, limiting the compounding effect of water over time – up to a point. And now they can identify that point.

With all of this information at hand, SARA can focus their protection efforts on the critical facilities they identified as susceptible to flooding, in particular low-lying roads and crossings. They can see that specific street and residential areas would likely see more extensive flooding, but the city’s tunnel system will also be able to mitigate some of the impact.

“It’s terrible,” Graham told the council about the resulting San Antonio super storm model. “It would be an event of record, but I don’t think it would have been quite like what Harris County saw.”

Go deeper into the story

- 27 trillion gallons of rain over Texas and $75 billion in damages. Read details about the aftermath of the devastation of Hurricane Harvey and see before-and-after photos.

- The last hurricane to hit the Middle Texas Coast did so in 1970, when weather forecasting was much less advanced. Now, it’s much easier for the National Weather Service to track and document these massive storms.

- You can do your own modeling like this using weather data and resources from the USGS that document the storm.