New regulations are challenging Florida water utilities to tighten up and ultimately eliminate all non-beneficial surface water discharges. CHA Consulting has been working to help utilities across the sunshine state find the right balance and stay ahead of statewide deadlines for compliance. Many thanks to co-author of this piece Project Engineer Parsa Pezeshk, who shared his knowledge of SB64 to help us understand what’s at stake for water utilities, and what options they have to meet the legislation’s ambitious deadlines.

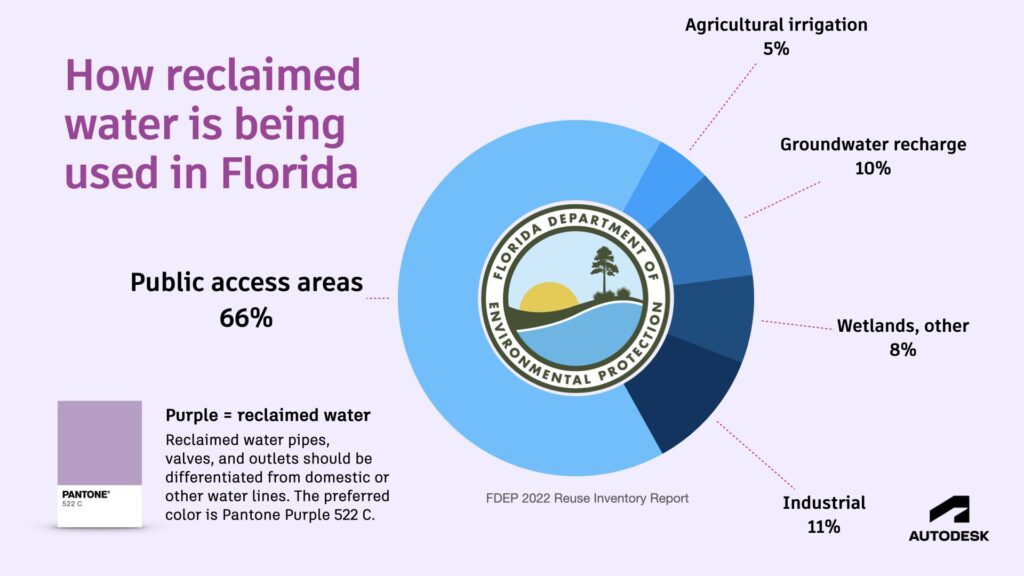

According to South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD), an average of 908 million gallons of reclaimed water (RCW) is reused in Florida every day, making Florida one of the leaders of Public Access Reuse (PAR) in the United States. But from that water success story springs new challenges, especially during rainy seasons, when the need for reclaimed water by customers for irrigation and other non-potable demands can lead to issues with oversupply and the need for storage or release.

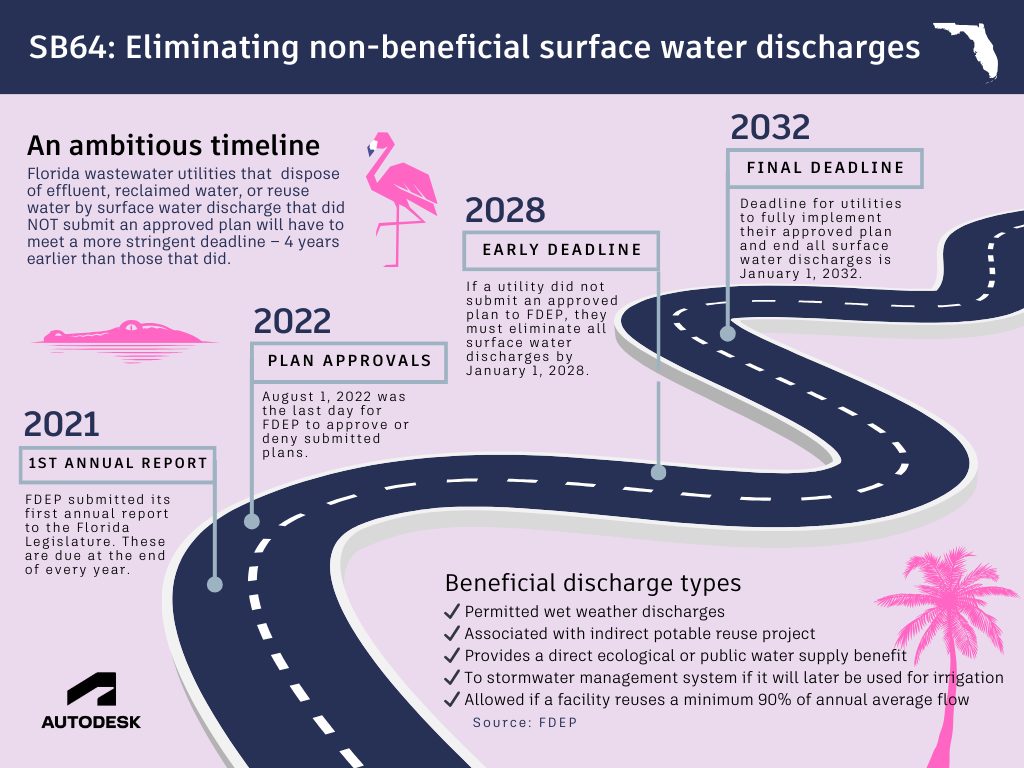

To bring more balance to the inflows and outflows, a new Florida water regulation was signed into law by Governor Ron DeSantis in 2021. SB 64 requires domestic wastewater utilities to reduce and ultimately eliminate non-beneficial surface water discharges by 2032, with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) overseeing the process.

Sweeping legislation with tough timelines

It’s noteworthy that SB64 passed through both chambers of the Florida Legislature unanimously. At that time, local news stories from around the state regularly documented high-profile sanitary sewer overflow events and eutrophication situations caused by red tides. This put an enormous amount of pressure on both state politicians and governing bodies to make significant progress on water reuse regulations while avoiding carving out exemptions for water utilities.

The final legislation set a November 2021 deadline – just four months after the bill was signed – for utilities to submit a plan to the FDEP that details their compliance methods. If they were unable to submit a plan by then, their deadline for full compliance moved up aggressively from 2032 to 2028, meaning they would have four fewer years to realize their plan. This was extra difficult for some utilities because their capital improvement plans have long timelines that require approval six years in advance, leaving them little room to pivot.

How the legislation is designed to work

Historically, reclaimed water, also known as highly treated wastewater, has been utilized in Florida for irrigation purposes for areas with reclaimed water pipe infrastructure. The excess reclaimed water is typically discharged to a Rapid Infiltration Basin (RIB) or to surface waters. To meet the requirements of SB64, domestic wastewater utilities that dispose of effluent or reclaimed water by surface water discharge are required to submit a plan that shows:

- Average gallons per day of surface discharge that will be eliminated, along with a target date

- Average gallons per day of surface discharge that will continue

- Level of treatment provided for reclaimed water/effluent that will be surface discharged

While this arguably unfunded mandate could be seen as a negative for the regulated community, there will be some tangible benefits coming, namely that more and more water will be reused, which will reduce pressure on the state’s resources as it continues to grow at a rapid rate. But it will require a lot of hard work from water utilities, who will need to foster innovative projects to supply the additional 1,100 million gallons of water per day that Florida will require by 2035.

There are some interesting details in the legislation. For example, it includes an explicit characterization of potable reuse as an alternative water supply with incentives to develop potable reuse projects. It also intentionally supports the concept of “One Water”, the idea that water is a finite resource that should be managed comprehensively as a whole, as opposed to being managed in silos as potable water, wastewater, stormwater, etc. Framing legislation like this could become a template for other US states who want to expand their use of reclaimed water.

Beneficial vs. non-beneficial uses of effluent

The details of the legislation provide for a mix of strategies and tactics for a utility to reduce its level of effluent. How a utility accomplishes their goals often comes down to the distinction between beneficial use vs non-beneficial use.

In the category of beneficial use, if it’s connected to a stormwater management system, you can use it for irrigation. Other beneficial uses include potable aquifer recharge, putting into the ground at locations designated as RIBs, use the water to maintain minimum river flows, or – if you’re ambitious – potable reuse.

Still allowable, but perhaps less desirable, is to release it into non-potable aquifers as an Aquifer Recovery (AR) solution into a permitted Underground Injection Control (UIC) well, or to store it underground and pump it back out again, known as Aquifer Storage and Recovery (ASR).

But if you rely heavily on what is considered non-beneficial use like Deep Injection Wells, you’re almost certainly going to need to decrease your outfall in larger ways to meet the regulations.

This, of course, is why you hire the right consultant to help you analyze your shortfall, assess all your options, and come up with strategies to ensure you both meet the requirements and improve your system. The right consultant may also be able to help you find funding in the complex warren of national, state, and local grant schemes – which is something that CHA Consulting is good at.

The growing importance of interconnections

This new regulation presents many challenges to reclaimed water distribution networks, but it may also encourage more sharing of water via interconnections, an increasingly popular water management strategy that allows water to be redistributed between neighboring water systems. This could become an important trend because some utilities regularly deal with more supply of effluent than they have customer demand, while others are faced with a deficit of reclaimed water for irrigation purposes. Interlocal agreements for importing and exporting reclaimed water can help them solve these problems and balance their surpluses and deficits.

Hydraulic models are valuable tools to analyze the design requirements and location of such interconnects, and more hydraulic modeling will probably need to be done because new developments are increasingly required to utilize reclaimed water when available. This has encouraged more developers to install separate piping system for their irrigation systems, which the developer can handily change from potable water to reclaimed water when a reclaimed water service becomes available.

How CHA measures fluctuating demand patterns

Getting an accurate picture of water demand is important, but it can be challenging for water utilities to develop diurnal demand graphs because demand patterns vary based on the usage type. Not only can understanding patterns of diurnal usage be tricky, but there are also two additional factors to consider when optimizing water reuse: What do you do during wet weather periods when people are not irrigating? And how do you deal with “excess” water in your reclaimed water system? There can be other additional factors influencing demand, but these can be accounted for with the right tools and data.

To begin with, irrigation for residential customers typically occurs during the morning and early evening hours, which correspond to the peak demand period. Utilities also typically prescribe a schedule for customers to water their lawns based on the customer area or the street address (eg, even/odd numbered) to manage the peaks and reclaimed water supply. On the other hand, large users such as golf courses are allowed to use reclaimed water during off-peak periods to reduce the stress on the system.

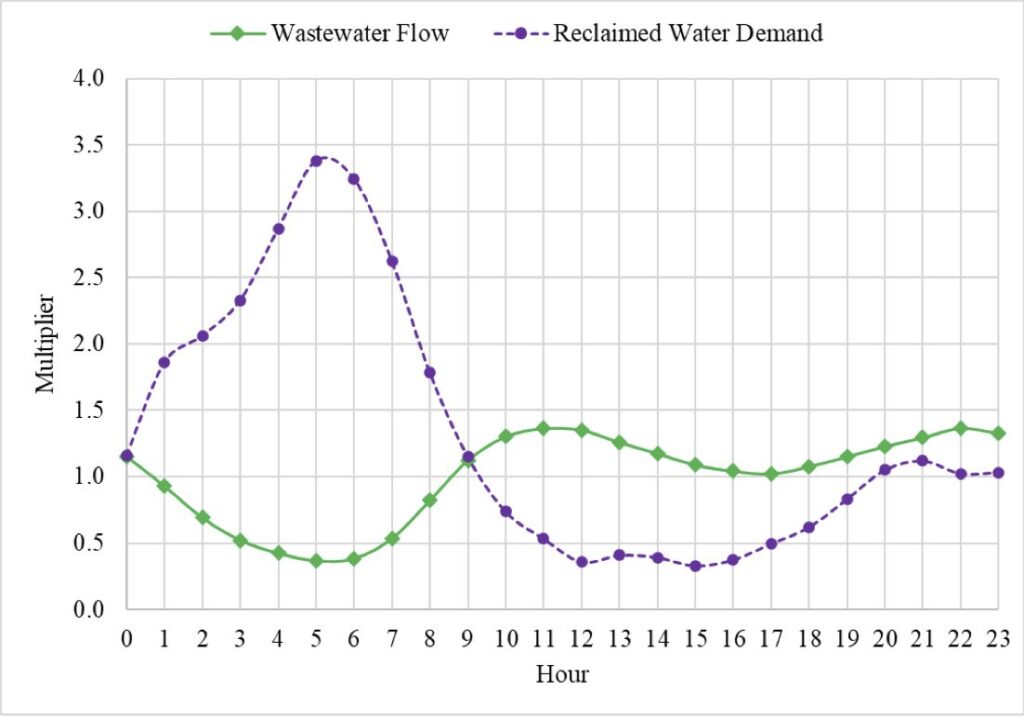

A further challenge faced with balancing the reclaimed water supply and demand is the difference between the diurnal pattern for reclaimed water flows leaving the Water Reclamation Facility (WRF) and the diurnal pattern for irrigation demand in the reclaimed water distribution system. Since wastewater flow to the WRF is the source of RCW, the RCW supply diurnal pattern resembles that of the wastewater flow to the plant.

Peak reclaimed water demands typically occur from midnight to the early hours of the morning when the reclaimed water source (wastewater flow to the WRF) is at the lowest. This issue signifies the importance of reclaimed water ground storage tanks, which are typically filled during the day from the WRF when the reclaimed water demands are lowest and drained during peak hours to supply the reclaimed water demand. It is also often the case the reclaimed water is pumped from a WRF to a Storage and Repump Facility (SRF) in another area of the distribution system to provide local high demands during peak demand period (to reduce the stress on the WRF pumping).

How CHA formulates a city’s water reuse capabilities

The first step to complying with the regulation is understanding the current state of a utility’s reclaimed water distribution network and its uses, which in Florida may typically include residential and golf course irrigation, groundwater recharge, and agricultural irrigation (eg, citrus crops).

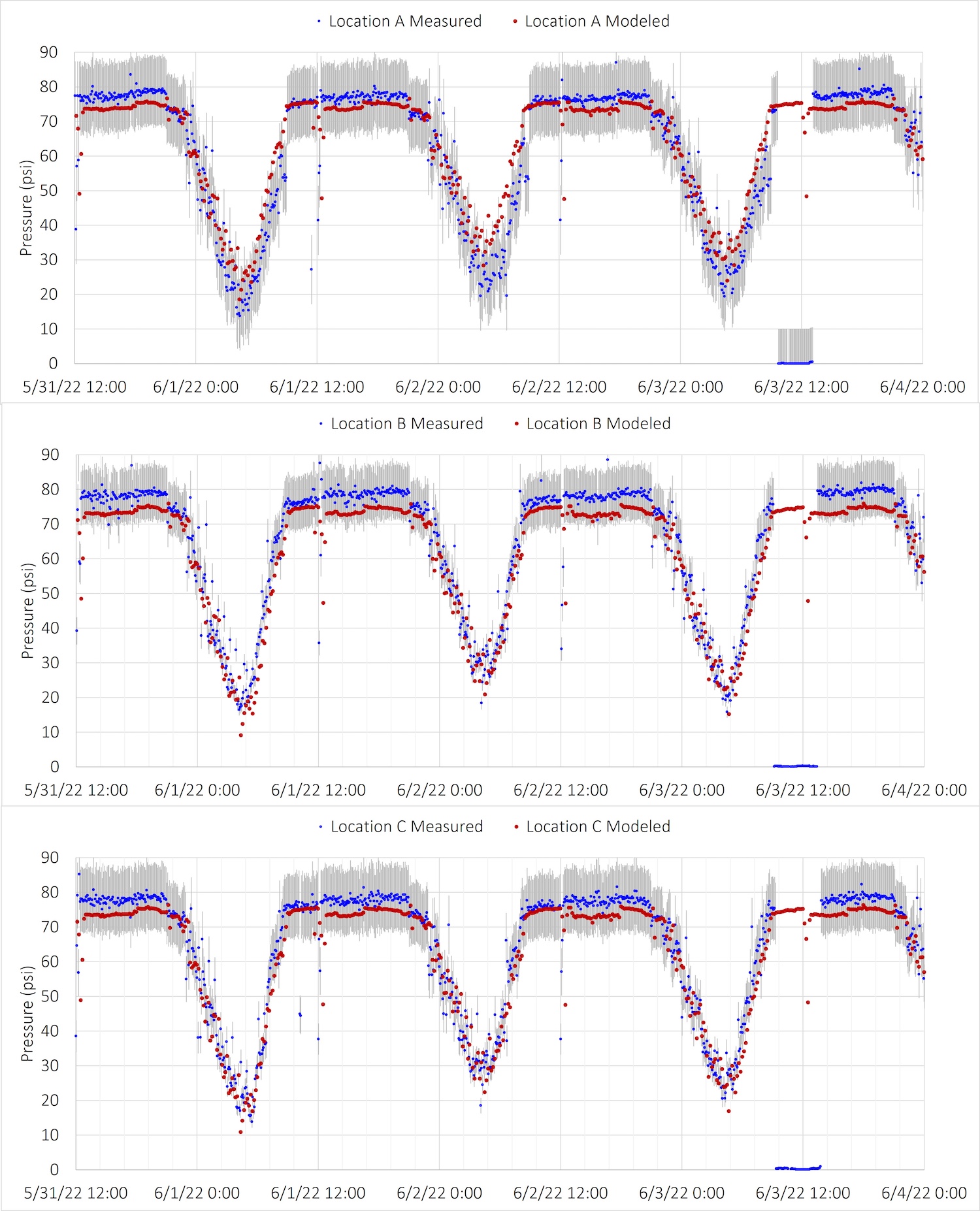

Given the complexity of existing reclaimed water systems and the need to understand demand and usage applications, CHA Consulting takes great care to build, calibrate, and perform detailed analyses using InfoWater Pro, hydraulic modeling software developed by Autodesk.

To build the model in InfoWater Pro, all network assets and their corresponding properties are imported from the utility’s provided GIS data into the hydraulic model using the InfoWater Pro’s user-friendly GIS Gateway. To validate the hydraulic model results, an extended period simulation is performed to match the modeled pressures to those recorded in the field, ensuring that the digital twin of the network accurately represented field conditions.

Based on the model results, CHA can establish that a reclaimed distribution system behavior can be adequately simulated using the newly build hydraulic model in InfoWater Pro. This model can act as a digital twin of the system and be used in simulating scenarios.

The journey to compliance

With this model in hand, a reclaimed water network can be holistically analyzed to understand historical incidents and predict future scenarios to ensure they always comply with the legislation. CHA Consulting can help utilities use an InfoWater Pro model to overcome challenges like determining what to do with excess water during wet weather periods, how to deal with regularly occurring excess water, and how to optimize operations to meet the expected level of service to customers during normal operation. The software can also help them perform highly accurate surge analysis and manage pressure zones to ensure their system runs smoothly.

These InfoWater Pro models can also be crucial to developing a plan for the FDEP, helping to justify the decisions presented to the EPA. It is also very useful for providing back-up supporting analysis and documentation. Having a digital twin model also ensures that the feasibility of future proposed solutions is high, reducing the need for rework and leading a city to be more efficient with its water resources while still complying with regulations.