& Construction

Integrated BIM tools, including Revit, AutoCAD, and Civil 3D

& Manufacturing

Professional CAD/CAM tools built on Inventor and AutoCAD

In The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, the character Gollum is an entirely digital creation based on the performance of actor Andy Serkis. Serkis was initially cast to give Gollum his voice alone, but as he worked, director Peter Jackson realized his movements would translate beautifully to the screen. This process, called motion capture (mocap) or performance capture (US Site), wasn’t invented by director Jackson—an early version of it, rotoscoping, was notably used back in 1937 for Disney’s Snow White.

In The Two Towers, as in Snow White, performance footage was referenced by animators for matching the timing and movement of Serkis in live-action footage. Jackson’s films achieved new levels of realism and detail two decades ago for the Rings trilogy and King Kong, winning visual effects (VFX) Oscars for The Two Towers and The Return of the King.

The essential elements of performance capture technology haven’t changed since then, according to Erik Winquist, VFX supervisor at Wētā FX, the company that’s driven performance capture forward in the aforementioned films, as well as the Avatar and Planet of the Apes series, among others. “Fundamentally, we’re still taking a talented human actor, putting markers of some kind on them, setting them on a stage, and recording what they’re doing,” Winquist says.

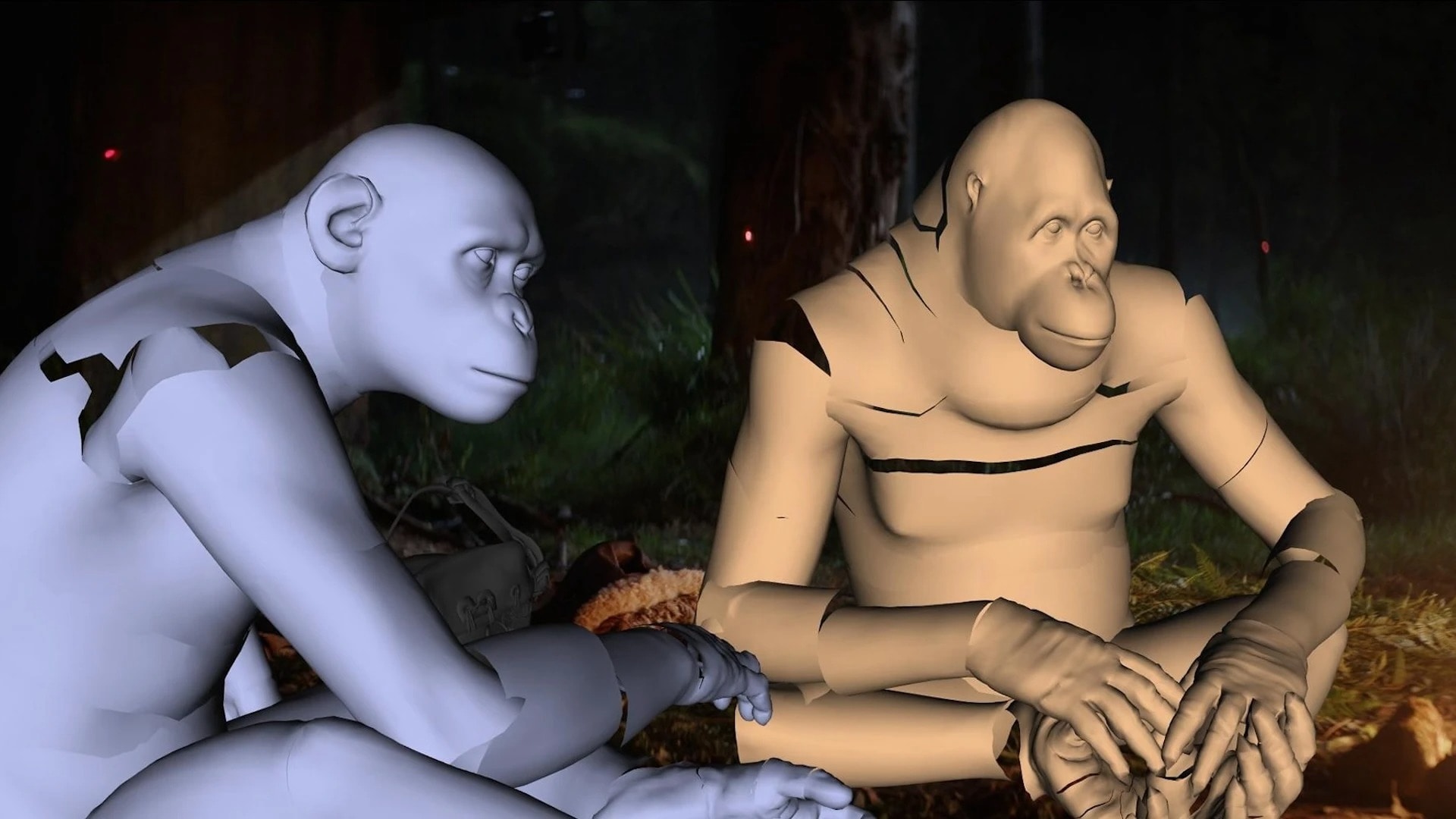

With the latest mocap technologies, Wētā FX crews can capture performances filmed outdoors in daylight or even in harsh environmental conditions. Image © Disney.

VFX artists say their best work is invisible. The bar for realism is high, and audiences can be unforgiving when VFX is even slightly off. For this year’s Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, the performance capture is seamless—viewers can experience realistic talking apes on-screen, interacting with props, live-action characters, and each other.

One of the biggest challenges Winquist and his technical crew solved for 2011’s Rise of the Planet of the Apes was the ability to take mocap outdoors, off a stage set. “Mocap technology is based on infrared, and sunlight has a massive infrared component to it,” he says. “As soon as you go outside, you’re fighting the infrared light reflecting off everything.”

The mocap team needs what Winquist describes as “white dots in a sea of black” for a detailed capture, the dots referring to the markers attached to mocap suits worn by actors. On an indoor stage, you can use artificial light with no infrared so the camera can easily pick up the suit markers. The answer to taking performance capture outside has been improved markers.

The latest-generation markers are tiny LED light sources that fire in sync with the camera shutter, isolating them and filtering out all other infrared sources. Camera operators can adjust exposure settings so infrared in the sunlight isn’t even picked up.

However, active LED lights can be fragile. For 2014’s Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, Wētā FX encased wiring in protective rubberized strands so it could be taken outdoors in the damp forests of Vancouver, Canada. For 2017’s War for the Planet of the Apes, the protective casings allowed Wētā FX to capture performances in even harsher environments such as snow and water.

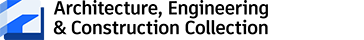

Stereo capture of actors’ performances and facial expressions makes it easier for Wētā FX animators to apply 3D character meshes to actors in a live-action frame. Image © 2024 20th Century Studios, courtesy of Wētā FX.

Other advancements to Wētā FX’s mocap processes include fitting more tech into the facial rig to pick up more detail and using two cameras to better capture that detail. In the same way that 3D films give the illusion of depth because of barely perceptible differences between two images, using two cameras gives animators a more accurate 3D mesh of the actor’s face, providing much finer detail than a single lens.

This breakthrough was crucial to Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes because of the unique way primates move their faces. “When an actor purses their lips or their lips extend or protrude, especially with apes when they’re doing their hoot sound, all those things can be tricky with only one camera; there’s a lot of guesswork,” Winquist says. “A 3D mesh gives us a lot more precision.” Successfully animating such movements—creating simian characters that live, breathe, and speak in a way that’s faithful to real apes—shows how far performance capture has come.

The new technology also removes the need for manual 3D depth compositing. Stereo capture on the facial rigs and the regular cameras meant Wētā FX could create a 3D mesh of anything in the frame, not just the actors. This greatly improved the match-moving process, where a 2D animated object is put in a live-action frame. “Eight major characters were interacting with real props like weapons or turning pages in a book,” Winquist says. “Keeping those movements from the main footage but replacing the character that’s doing the interacting with an animated element becomes a lot easier when you know exactly where it’s going to be in 3D space.”

Through performance capture and CG animation, the character of Noa in Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes retains all the subtle elements of actor Owen Teague’s performance. Image © Disney.

The key element in the performance-capture process is still a performance—an actor moving and behaving as a character. It was largely Serkis’s exploration of a skittish, spiky personality that made the character Gollum work so well in The Two Towers and The Return of the King. For Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, star Owen Teague studied ape movement at a primate sanctuary to bring authenticity to his performance.

When Serkis told the media about the upcoming Rings project The Hunt for Gollum, he said the technology is actually freeing. “It’s now reached a level where the authorship of the performances allows you to actually internalize more without any sense of overacting,” he said. “This is something that is clearly working at a much greater and a deeper level now.”

But there’s a caveat now that a director can watch a scene on a tablet as it’s being performed, with the character rig applied to performance-capture data in real time. Winquist says: “A filmmaker doesn’t need to focus on the ‘apeness’ of it—we can make all sorts of postproduction adjustments, like make a character taller or fit in the frame better. The biggest thing to focus on is the nuance of what’s happening on the actor’s face, the subtlest little microadjustments. I’d be concerned about sanding off the rough edges that make a human performance what it is. If the director can’t see that because they’re looking at an approximation with a real-time low-res proxy facial rig applied, they won’t have the information they need to decide if take 5 or take 6 is better.”

Winquist adds that no matter how good the technology gets, the director and animators need to really see what the actor’s giving—subtle eye movements of just a couple of pixels means everyone can see “the gears spinning.”

There is a balance where performance capture on set and CGI augmentation during postproduction coexist. “There are moments where we have to invent something the director didn’t get on the day of the shoot for whatever reason,” Winquist says. “They say the film’s really made in the editing room, and someone often says, ‘If we knew then what we know now, we could have shot this differently—but, hey Wētā FX, can you help us?’”

Again, everything comes back to the performance. “Our animators are insanely talented, but there’s something in that space between a director and an actor,” he continues. “That experimentation happens then and there. If you pass it off to VFX, there’s still a lag to turn an update around, even if it’s just a couple of hours. By then, that magic that only happens on set; that spontaneity is gone.”

Wētā FX used a facial deep learning solver (FDLS) to efficiently generate initial performance-capture renders, freeing its artists to focus more time on the challenging work of expressing spoken dialogue on apes’ faces. Image © Disney.

After many years in this field, Winquist says the company’s rendering pipeline is well-established and streamlined, so his team can render things to look “absolutely, unquestionably real.” CGI milestones during the 2000s saw surfaces like water (US Site), fire, and hair finally “conquered.” Now, the focus is on how to make CGI and VFX more efficient to produce. “To some degree, it’s the same as when you get a new hard drive, and you just keep filling it up,” he says.

Performance capture is one of the most data-intensive areas of modern VFX, making it a natural fit for machine learning. Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes had more than 1,500 VFX shots, most containing performance-capture data. There are only 38 shots that contain no VFX at all—a far cry from 2002, when Gollum had 17 minutes of screen time in The Two Towers.

Using machine learning, Wētā FX developed a facial deep learning solver (FDLS), where algorithm-directed performance-capture renders are verifiable by humans throughout, rejecting the “black box” nature of most machine learning tools. After shots are approved, it lets animators stream the results directly to tools within an editing or animation application. Wētā FX uses Autodesk Maya as a platform to house some of its proprietary visual effects and animation tools.

Wētā FX’s advances in machine learning technology are made with the goal of empowering its artists to do more. “We wanted to rely on the same core crew we’ve been using, but creating spoken dialogue on apes’ faces gave them a lot more work to do,” Winquist says. He adds FDLS helped the Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes animators get a consistent baseline for each character that could be applied to multiple shots.

In a performance-capture workflow, it all comes back to the nature of the story and the production style. “If you have a character over a few dozen shots, it changes your approach because motion capture comes with a very large footprint—suddenly, you have 40 crew members to carry around with you,” Winquist says. “If you have a single character, you could have a much lighter footprint on set and work much more efficiently. So a big consideration when we come in is the technology that’s the best fit for a particular show and budget.

“We evaluate the needs of a particular project and make our plan accordingly,” he continues. “We can bring a full-blown capture system to a soundstage or outside location, or we can just rock up with a couple of video cameras, throw slightly different markers on the performers, say ‘Action,’ and sort it out later.”

After growing up knowing he wanted to change the world, Drew Turney realized it was easier to write about other people changing it instead. He writes about technology, cinema, science, books, and more.