3D printing concrete: A 2,500-square-foot house in 20 hours and an eye on a moon Shot

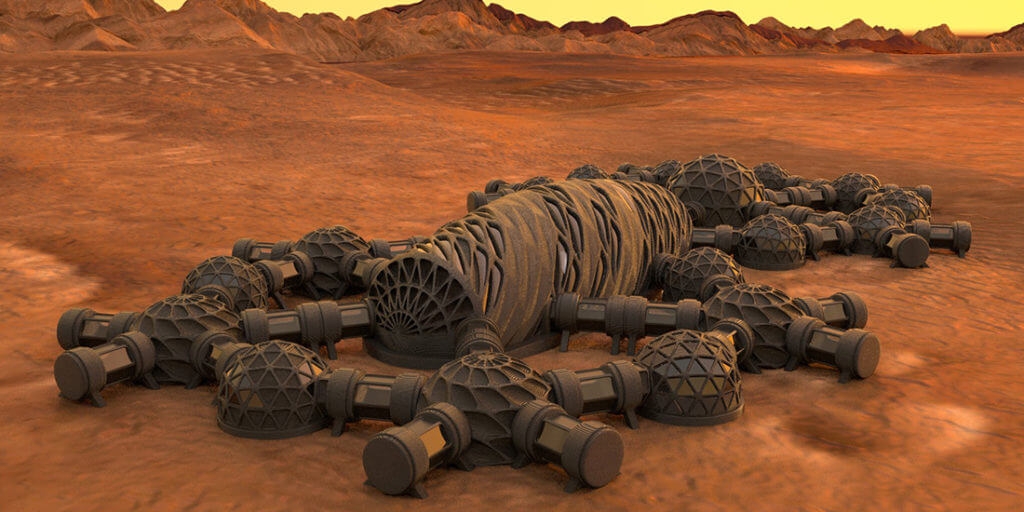

Learn about Contour Crafting for 3D printing concrete. It can build a single 2,500-square-foot house in about 20 hours and potentially a space colony.

Spend a minute or two on the Internet, and you’ll find 3D printing can be used to build all sorts of things: automobile parts and prototypes, prosthetic ears, stem cells, submachine guns, eyeglasses, and even desserts customized to one’s nutritional requirements.

But what about building construction? Why couldn’t these same methods be adapted to build actual-scale civil structures—single-family homes, commercial buildings, even large settlements—with greater speed and efficiency?

A house in 20 hours

That was just what Behrokh Khoshnevis says he envisioned when developing Contour Crafting (CC), a 3D concrete-extruding printer that can be used to build a single 2,500-square-foot house in about 20 hours.

Khoshnevis is a professor of industrial and systems engineering at the University of Southern California and the director of the Center for Rapid Automated Fabrication Technology (CRAFT). His lightning-quick fabrication process for 3D printing concrete, under development with federal funding from the National Science Foundation and the Office of Naval Research, has the potential to revolutionize the construction industry, saving time and building costs and reducing injuries at the build site.

Seeing a single wall being erected using CC is sort of like watching icing being squeezed onto a cake. A robotically controlled nozzle guided by a CAM application emits ribbons of wet, fast-drying cement, one layer at a time.

The genius of the system is a pair of trowel-like fins attached to the nozzle that spread and shape the concrete into smooth forms. The adaptation of the trowel for 3D printing is an epiphany that struck Khoshnevis in 1994 while he was fixing cracks in his living room after the Northridge, California earthquake.

The innovation greatly improved speed and surface quality and gave Khoshnevis the idea he could scale up 3D printing and bring it into the realm of construction. “At the time I wasn’t thinking about 3D printing for buildings,” Knoshnevis says. “I just wanted to build faster. When I noticed the speed could be orders of magnitude higher than other 3D-printing methods, it made large stuff practical.”

Large stuff like the molds for ship propellers and submarines he was creating at the time; then, in 2004, the first contour-crafted walls, and, if all goes as planned, the first full contour-crafted house, on schedule to be built on the University of Southern California campus by summer 2016.

How it works

With CC, the 3D printer, mounted on an elaborate, six-meter-tall gantry resembling an oversize sawhorse, is just one piece of a much larger system. The machine lays down lines of concrete, layer by layer, climbing as it builds: in essence, “printing” a house. The system is highly adaptable. In a more complex configuration, the gantry can also ride horizontally back and forth on train-track-style rails to construct a series of homes or an entire neighborhood. Conduits for electrical, plumbing, and air conditioning are embedded into the hollow-wall structure. Finishes, tiling, interior work, and a chain-like roll-out metal ceiling can also be included in the structure. A video on the CC website illustrates the entire process.

Khoshnevis isn’t the only one using 3D printing to test the boundaries of the construction industry. Earlier this summer, MX3D unveiled plans to 3D print a pedestrian bridge with multi-axis robots, and the Minibuilders project shows how a team of robots can build human-scale structures out of a marble and polymer composite.

Yet, Khoshnevis’s project is rare in the breadth of its potential applications and the scale or its ambitions. Houses remain one of the few things still built by hand, Khoshnevis says. Shoes, clothes, and home appliances have all seen their fabrication automated. And despite the opposition of critics who fear 3D-printed homes could eliminate professional building jobs—a threat Khoshnevis does not entirely deny—he believes houses are next in line for scaled-up automation.

Low-income and emergency housing

Khoshnevis, who emigrated from Iran in 1974 and holds more than 70 patents in fields ranging from aerospace engineering to robotics, sees applications for CC in commercial construction, low-income and emergency housing, and autonomous space colony construction. The prolific inventor—who is also a NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts fellow—has even devised a proposal for sintering moondust to form a landing station for future spacecraft.

Back on Earth, CC could be used for the building of a single house or multiple houses, each with a potentially different design, in a single run. The prototypes are inordinately strong, with a pressure tolerance of 10,000 psi—three times that of a typical home, making them particularly well suited for earthquake and hurricane-prone regions of the world.

And because CC’s labor, financing, and material costs are so low, Khoshnevis says the process could be applied broadly to print affordable housing in poor developing countries: “When we manage to make them economically available to poorer regions, in slums, hopefully we can respond to the needs of these areas.”

While one might worry that scaled-up concrete automation could lead to cold, homogenous design, Khoshnevis says on the contrary—CC allows for elegant geometric structures as shapely as some of the most elaborate early adobe structures in his native Iran.

Due to the astounding speed at which buildings are printed, the process could also upend wasteful practices of a construction industry, notorious for long-distance material delivery and lengthy installation that contribute to high levels of carbon emissions. By limiting the number of workers on a job site, the process could even save lives, Khoshnevis said in a February 2012 TEDx Talk in Ojai, CA, citing the 400,000 people injured and 6,000 killed in construction accidents in the United States each year.

While finding funding and gaining regulatory approvals has been difficult, Khoshnevis admits, the technology brings a combination of cost efficiency, speed, and architectural flexibility that, to his mind, make it a worthy investment. “The reality is it will take time,” he says. “Construction is a very conservative pursuit, and rightfully so. ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’ The practices being used today are not the most efficient and productive, but moving into a new paradigm is disruptive and risk prone.”

Not that Khoshnevis is afraid of disruption, especially if it brings about economic growth and mobility. As he concluded in his TEDx Talk to a round of hearty applause, “In 1900, 62 percent of Americans were farmers. Today, it is less than 1.5 percent. The world did not come to an end. There will always be better economies because of advancement and the utilization of technologies that just make sense.”

About the author

Jeff Link

Jeff Link is an award-winning journalist covering design, technology and the environment. His work has appeared in Wired, Fast Company, Architect and Dwell.