Fashioning the future: How digitalization can help the fashion industry reduce waste and increase opportunity

Learn how the digital transformation of the fashion industry is making it more efficient, sustainable, and accessible.

Matt Alderton

October 31, 2024 • 12 min read

Fashion brands have been slow to adopt technology but quick to embrace mass production. The result: an industry that thrives on waste.

A new generation of digital tools is poised to finally transform the fashion sector by reducing inefficiency and increasing opportunity.

Fashion’s digital future depends on interoperability and professional collaboration as vehicles for industry cross-pollination.

Fashion has always been an analog business. It’s easy to understand why. From the shimmer of a sequined gown, and the vibrancy of a neon T-shirt, to the buttery softness of a cashmere sweater, fashion is tangible, technical, and tactile. It is seen, sampled, shaped, and sewn.

Like many analog industries, however, fashion has reached an inflection point. Behind it is the way things have always been done. In front of it, a vision for how things might be done better. And in between, an opportunity to use digital transformation as a bridge from past to future.

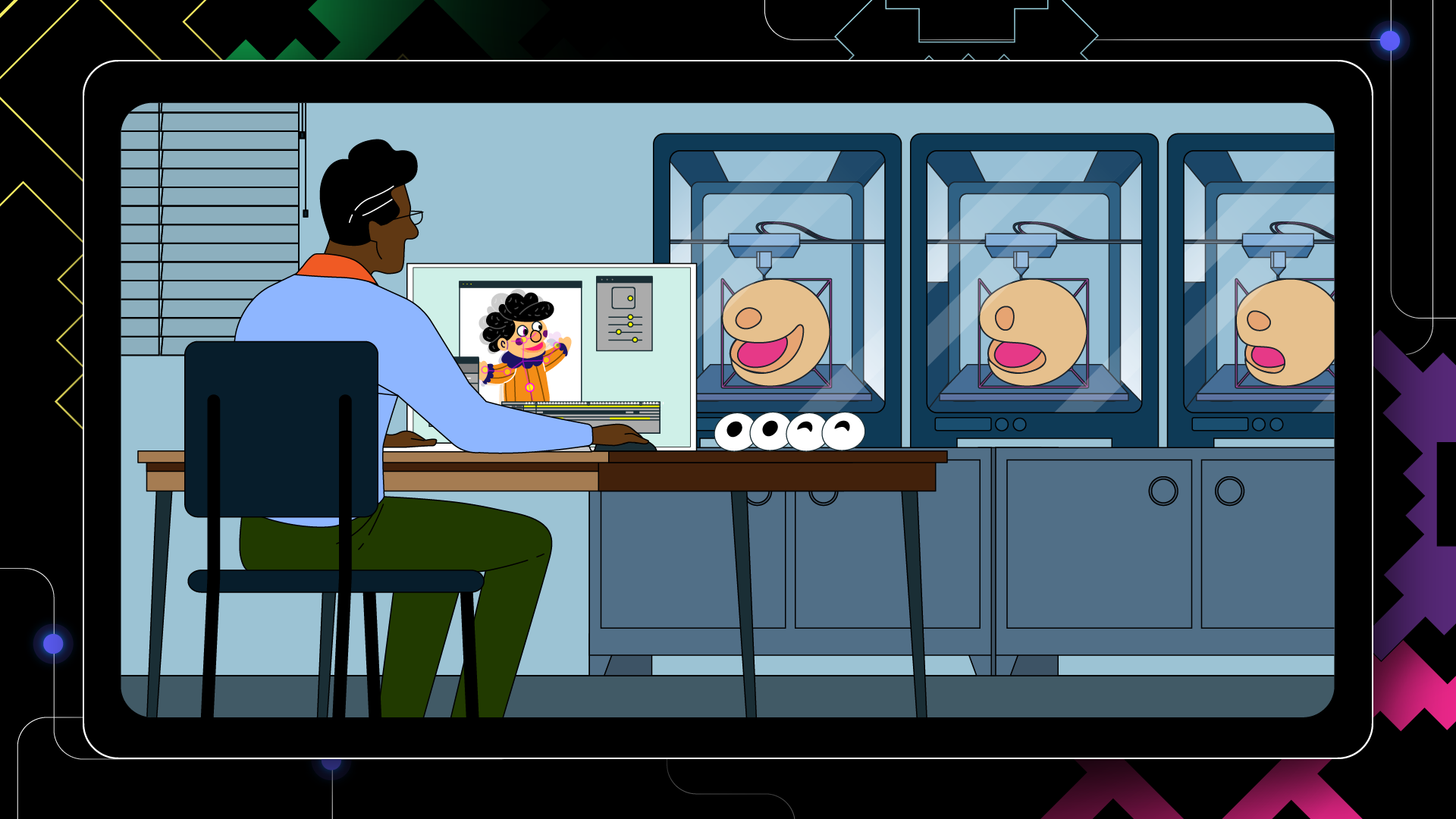

British fashion executive Louise Laing is leading the charge across that bridge—in fact, she’s one of the people building it. In 2022, she set out to modernize the fashion industry by using digital tools to reduce waste and improve efficiency. Her London-based startup, PhygitalTwin, leverages 3D technology and artificial intelligence to help major fashion brands digitize their collections and to help individual creators turn digital designs into physical garments.

Because technology is still largely new to the design industry, the low-hanging fruit at this stage of Laing’s business is 3D modeling. “3D visualization makes product development shorter,” Laing says. “You don’t have to ideate five different samples until you get the right one. You can see something much more clearly through the 3D mesh. It has more structure. You can put fabric on it to see how the fabric will drape before you actually sample it.”

Sampling—the act of making and refining physical prototypes of garments before mass-producing them—is just one area where digital tools can make a big impact in fashion. Digital transformation could help the fashion industry remake its entire supply chain through concept, design, manufacturing, production, sales, and marketing.

From wearable to wasteful

To appreciate fashion’s future, it’s necessary to understand its past, according to Chris Baeza, associate program director and assistant teaching professor of fashion industry and merchandising at Drexel University.

Though the modern fashion industry has roots dating back to the Industrial Revolution, Baeza traces its more recent history to 1994 when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect, opening the door to US companies operating overseas. After NAFTA, Baeza says, American apparel brands moved their production en masse to Asia in pursuit of cheap labor, low taxes, and reduced oversight. That led to the birth of “fast fashion”—the mass production of cheaply made clothing that can be purchased off the rack in any size for a low price.

“When NAFTA was passed, it dramatically transformed the textile and fashion industries in the United States, shifting much of the manufacturing overseas and leading to a surge in clothing consumption,” Baeza says. “Before, people typically had maybe two pairs of jeans. Now, many of my students report having 15 to 30 pairs of jeans in their closet. Clothes are cheaply made, so they rip and tear easily and ultimately end up in a landfill.”

Waste is rampant at every link in the fast-fashion supply chain, Baeza points out:

To create garments, fashion designers test and iterate with physical fabrics, generating scraps of discarded textiles.

At the production stage, factories also have to test and iterate, which creates even more scraps.

Retailers, meanwhile, place massive orders for garments to make sure consumers can get the items they want in their desired size and color. When the season ends, their stores and warehouses are full of unpurchased items.

Finally, there’s e-commerce. When modern consumers buy products online, they don’t know how they will look or fit. That leads to excessive returns that once again end up in landfills.

Of course, it’s not just materials that are wasted. It’s also the fuel used to shuffle them between designers, factories, warehouses, stores, and consumers, which generates significant greenhouse gas emissions.

“The fashion industry is very tied to the oil industry,” says Baeza, who cites not only shipping, but also fabrics. “We’ve gone from natural fibers dominating the market to synthetic fibers that are petroleum-based. These synthetic fibers shed microplastics and can release harmful chemicals as they break down, contaminating our soil and water.”

Though it has been the norm for 30 years, it’s plain to see that fast fashion is not sustainable for the environment.

Turning the tables on tech in fashion

Technology could be the antidote to fast fashion’s ills. But the fashion industry is notoriously resistant to it, says Clare Tattersall, founder of Digital Fashion Week and The Drip. The former is a twice-annual event showcasing physical and digital fashion design, the latter an haute couture digital fashion boutique. “There hasn’t been a revolution in fashion since the invention of the sewing machine 300 years ago,” Tattersall says. “It really is a dinosaur industry.”

In recent decades, the digital revolution of computer-aided design transformed industries like architecture, aviation, and automotive. But it left fashion behind, says Baeza’s colleague, Nick Jushchyshyn, program director of virtual reality and immersive media at Drexel University.

“Until a few years ago, fashion was still a very traditional, hands-on activity,” says Jushchyshyn, who adds that digital technologies that came online decades ago were inaccessible and impractical for use in fashion until recently. “They were crazy expensive and weren’t as effective at being able to realize fashion design as they were mechanical design. Computers weren’t up to the task of rendering the image of a finished garment draped on a person in movement. And ultimately, that’s what fashion is about. Without the ability to visualize, you at some point were going to have to start cutting fabric, so it didn’t make a lot of sense to fire up a computer and go through all the trouble of a computer-aided design process.”

Because technology is finally fashion-ready, it now makes lots of sense. “Now that we have high-speed GPUs, software can simulate the look and behavior of various fabrics inexpensively on a desktop,” Jushchyshyn says. “You can design and prototype garments digitally, seeing them not just as 2D patterns but as they’d appear on a model. You can tailor designs to specific people using digital mannequins that match their exact measurements. These digital designs can be used with modern manufacturing equipment and some specialized digital production tools. This means garments can be manufactured more efficiently and in smaller lots—potentially even made to order.”

With that kind of digital workflow, designers and manufacturers alike can make alterations on the fly without wasting fabric or fuel. “If you’re designing a garment physically, there are discarded textiles as a result of that process. If you’re designing a garment digitally, you’re just discarding pixels,” Jushchyshyn says.

Retailers can use the same 3D modeling technology to save resources at the back end of the supply chain. “Why can’t you take a really good digital asset and put it up on your website to get a read on consumer demand before you go produce stuff?” Baeza says. “With better data, the industry can make better decisions and stop overproducing.”

Digital tools can likewise extend to applications like virtual try-ons. If people can accurately visualize how things will look and fit, they will make more purchases and fewer returns. In fact, a 2021 study by the virtual try-on platform Perfitly found that brands offering virtual try-on technology average 64% fewer returns.

“Customers have a much better idea of what they’re buying,” Tattersall says. “When they know what something is going to look like on them—or on an avatar with their same body type and shape—there’s a massive increase in the chance that they will purchase it. And when you couple that with the greatly reduced return rate, it’s a win-win for everybody. Customers end up with garments they like and there’s less waste in the environment.”

What’s good for the planet also is good for business. “When we design things virtually, it allows us to test quickly and make changes really fast,” Tattersall says. “That doesn’t just save resources. It also saves money, because all those materials that we’re putting in landfills have a price attached to them. That’s the very, very bottom line of this.”

The democratization of fashion

For creators, digitalization isn’t just about what can be saved—resources and money—but also what can be gained: new kinds of designs and new sources of customers.

“The idea of digital fashion began with software to help companies be more efficient and effective in their processes. But when you put these tools in the hands of creatives, they become something else,” Tattersall says. “Designers have used this software to create gravity-defying, extravagant, fabulous clothing. They’ve created a whole new world, and that’s pushing fashion to places it’s never been before.”

One of fashion’s new frontiers is the gaming industry. “The same tools that are used to design garments for physical production can export digital files for importing into tools that are used to produce video games,” says Jushchyshyn, who adds that digital renderings of garments can be made available as skins for game characters, opening up a new revenue stream for indie designers and big fashion brands alike. “For example, a design could be imported into Maya and animated, or it could be imported into Unreal Engine and be put into a game like Fortnite, where you can create a branded island where everyone is wearing your brand’s accessories and clothing. That’s beneficial from a marketing standpoint because you’re able to reach a whole generation of folks who aren’t accessible through traditional advertising on radio and television; multiplayer video games are where they congregate.”

Though some designs might exist exclusively in games—or just as likely, on avatars in the metaverse—what’s really exciting is the prospect of a digital-to-physical pipeline, according to Laing, who says artificial intelligence could help bring that to fruition by automating the process of converting digital designs into physical garments consumers could order from within a virtual environment and wear in real life. Imagine a crazy headpiece that defies the laws of gravity, for example. What exists virtually might not be possible physically due to the laws of physics, but AI tools like Phygital Twin’s AI engine could take the virtual design and automatically tweak it in ways that make it practical.

The digital-to-physical pipeline also excites Tattersall, whose Digital Fashion Week events include hologram runway shows, where digital avatars mimic human models’ movements in real time, as well as “phygital” runway shows that layer digital and physical fashion with the help of augmented reality, digital twins, and other 3D assets.

“Before I started Digital Fashion Week in 2020, technology was supposed to exist quietly in the background, if it existed at all. But now it’s front and center,” Tattersall says. “Our goal is to shine a light on what’s possible in fashion, and to make technology as sexy on the runway as clothes.”

In the not-too-distant future, that sex appeal will translate into real benefits, predicts Laing, who foresees a fashion industry that thrives on mass customization instead of mass production. In that world, consumers shopping in video games, in the metaverse, or in physical storefronts will be able to try on virtual clothing, customize it to their preferred color and precise fit, and then order it for next-day delivery from retailers that produce it on-demand in local and regional facilities stocked with fabric and automated production equipment.

“I believe in the democratization of fashion,” Laing says. “Everyone should be able to have some say over what they wear and how they wear it. Everyone should be able to be a designer and co-create their own fashion collections. The digital tools and technologies exist now to enable that.”

Collaboration is key

A more democratic and bespoke fashion industry would serve designers, brands, consumers, and the environment. Bringing it to fruition requires digital tools and also the standards and knowledge required to use them fully.

Step one is interoperability. “Interoperability is absolutely key to everything,” Tattersall says. “This has been a major frustration for designers and consumers. If you buy a digital asset, you want to be able to use it on multiple different platforms.”

Open-source standards like the Universal Scene Description (now known as OpenUSD) file format already exist for digital garments. Take z-emotion, a South Korea-based producer of 3D garment simulation technology. Its 3D apparel design software, z-weave, enables live virtual fittings with custom body avatars that help consumers visualize garments on their bodies. Used by brands like Nike and Louis Vuitton, it supports OpenUSD and integrates seamlessly with Maya thanks to z-emotion’s z-maya cloth simulation plug-in, creating a frictionless pathway between the fashion and gaming industries.

But assets still don’t flow freely because fashion designers lag in digital literacy, Jushchyshyn says. “The real hurdle is that it takes a lot of different tools,” he says. “If you have a fashion design tool, you probably wouldn’t use that to make a finished render to put on a billboard or a sign. Instead, you’d export that and put it into something like Maya, then render it there. So there are multiple tools, and they do communicate with each other. But there are multiple learning curves for a fashion designer to overcome.”

That’s where educators like Jushchyshyn and Baeza come in. At Drexel University, they’re cross-pollinating fashion designers with technologists by teaching them how to work together in shared workflows of mutual interest.

“We have fashion students who are interested in fashion, and we have digital students who are interested in film, game design, and animation. We’re bringing them together to collaborate and create,” Baeza says. “We’re combining the best of both industries in our classrooms because that’s what's going to change fashion for the better.”

About the author

Matt Alderton

Matt Alderton is a Chicago-based freelance writer specializing in business, design, food, travel, and technology. A graduate of Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism, his past subjects have included everything from Beanie Babies and mega bridges to robots and chicken sandwiches. He may be reached via his website, MattAlderton.com.