BIM helps Schneider Electric slash its energy bill in Grenoble, France

In Grenoble, France, Schneider Electric has constructed two buildings that surpass the country's 2012 Thermal Regulation standards and set new precedents for BIM and automation efficiency.

Maxime Thomas

June 28, 2018 • 6 min read

Schneider Electric is constructing two new flagship buildings in Grenoble, France, aiming to exceed the 2012 French Thermal Regulation targets by 20%–40%.

These buildings, targeting LEED Platinum status, will accommodate more than 2,000 employees and require more than $130 million in investments.

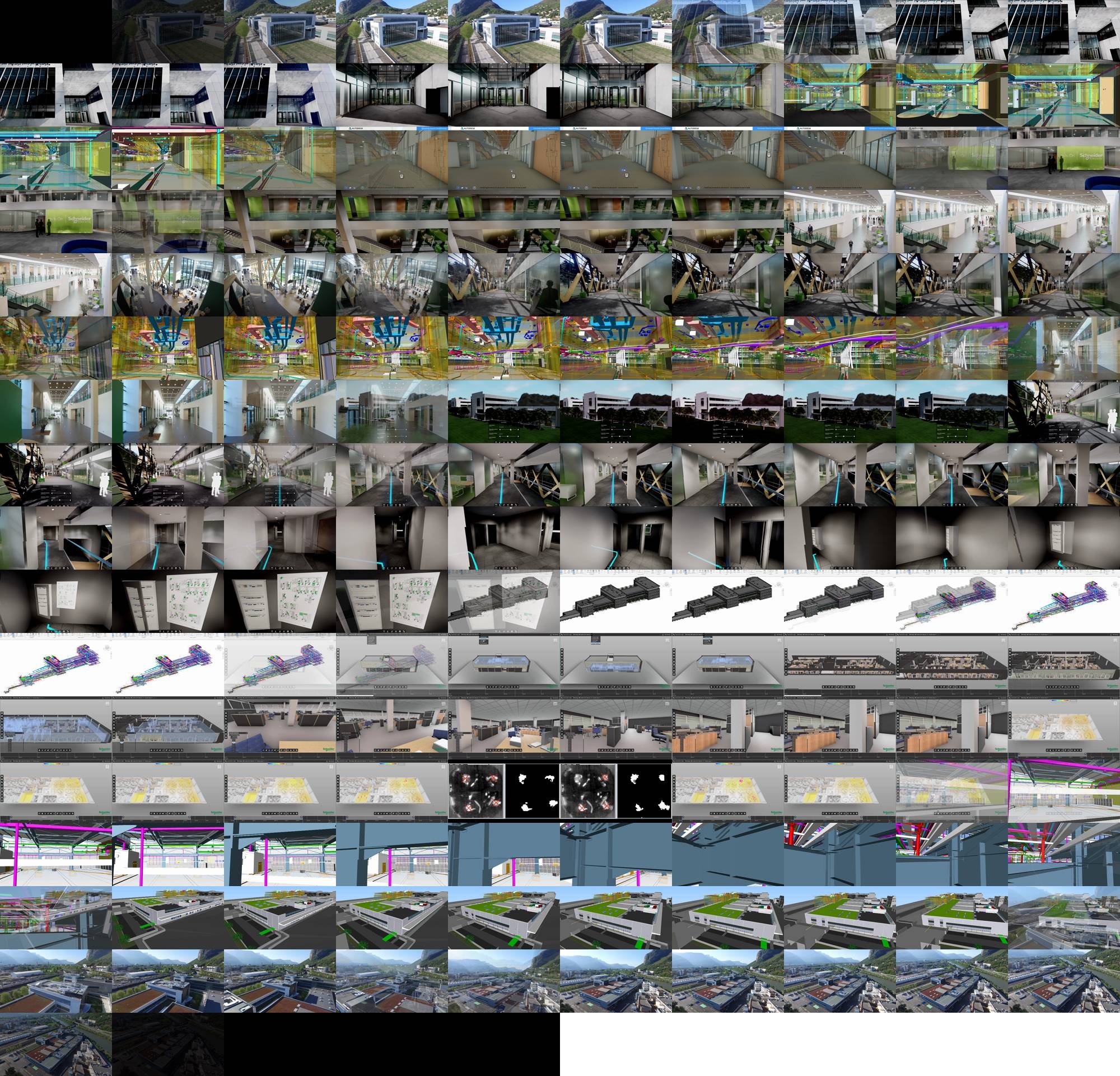

The project integrates BIM and building management systems to create a digital twin of the physical assets, bridging the gap between design and operational phases.

Innovative features include thousands of sensors and solar technology, aiming to significantly reduce energy consumption and set a new standard for efficient building operations.

The Dauphiné region in southeastern France has a storied history, from its time under Roman rule to its transformation in the early 20th century into one of the country’s most important industrial valleys. In the heart of the French Alps—now home to wine making, silk farming, and Michelin-starred restaurants—a company now called Schneider Electric was founded by two brothers in 1836, entered armaments and electric production in 1891, and is now a global presence in more than 100 countries.

Schneider, which employs about 5,000 people Dauphiné, is taking on a new challenge: surpassing the targets of the 2012 French Thermal Regulation by 20 to 40 percent in the construction of its two new flagship buildings in Grenoble. The buildings—one just under 120,000 square feet and the other at nearly 280,000 square feet—have to accommodate more than 2,000 employees and will require 120 million euro ($134 million) in investments to construct.

“This means we have to be innovative when it comes to setting a new standard for the group,” says Olivier Cottet, Schneider’s marketing and channels director of energy analytics. The two new buildings are in the running for LEED Platinum status, the top level of certification for sustainable development. Schneider Electric’s goal is to exceed the target of 100 points (110 is the highest rating)—a score that’s so far unsurpassed.

For efficient construction of the buildings, a key factor will be connecting the building information model (BIM) created using Autodesk Revit and building-automation software (also known as a “building management system,” or BMS) used to control technology such as lighting and alarms.

“We see a great advantage in connecting the database of static data of the building [BIM] and the dynamic database, including all operating systems [automation],” Cottet says. The connection between these two databases requires a specific structure of the two data sets, especially on the BIM side, and unleashing its full potential requires adjustments of the BIM model after the construction work has been completed.

“In fact, there is a real gap between the BIM used in the design stage and the BIM used in operations,” says Bertrand Lack, director of strategy and innovation for the building division at Schneider Electric. “Between these two lies the construction phase—and it’s during this phase, when the workers are on site, that they make do with what they have on hand.”

Making any adjustments on site won’t be reflected in the blueprints or in the digital model. These adjustments that take the “as-designed” BIM model to an “as-built” one are critical to ensure that the BIM model reflects the physical asset as its “digital twin.”

The reality that construction and operations worlds often ignore each other is a barrier the group is working to counteract, bringing together the philosophical and technical minds of two actually very similar fields. “During our research projects on energy performance, we realized that many of the buildings’ operational difficulties stem precisely from this organizational divide between the teams,” Cottet says. “It’s a treasure chest waiting to be discovered.”

Working closely with the general contractor GA Smart Building and the engineering office Artelia, Schneider Electric has tested a “contract for guaranteed results in preconstruction”—a commitment to meeting the energy-performance levels in the digital model. “Admittedly, it is quite complex. We have to take things one step at a time,” Cottet says. “The goal is to set up a digital twin of what our building will look like at the time of delivery.”

As the project has advanced, BIM has saved time for the teams, at a fixed budget. “It saves us money since it’s one of the tools that allows us to achieve our goals of reducing energy consumption,” Cottet says. “It was out of the question for our real-estate department to spend an additional €1 million under the pretext that we were going to build a high-performance building.”

Schneider Electric uses Autodesk software to create operating tools for future buildings, including monitoring interfaces that gather information on the building in real time.

As one of the buildings has already been completed, Schneider and its partners use it to understand the algorithms and features needed to reach the target of an average 45 kWh/m² per year. This has informed the construction of the second building, which is underway and is expected to lower the annual consumption further to 37 kWh/m2.

As a point of context, a late-2016 study by Skanska found that the average total electricity consumption of certified office buildings in Europe was 142 kWh/m². Schneider’s building performance is even more remarkable in a city such as Grenoble, where the average temperature in January can dip below freezing.

Several thousand sensors were installed in the first building with the goal of achieving precise facility management. “Another major undertaking for us is moving from big data to smart data: Too much data can lead to information overload,” Cottet says. “We’re therefore also working on how this data is presented so that we can get the most out of it.”

Schneider Electric has also included solar technology in these structures’ designs. The larger of the two new buildings will produce more energy than it consumes in a year, thanks to more than 43,000 square feet of photovoltaic panels on the roof.

In addition, integrating the Internet of Things (IoT) will provide more flexibility of control over the buildings’ temperature, lighting, air quality, and even power usage. Thanks to the IoT architecture, equipment can be controlled based on multiple criteria. “This flexibility will allow the consumption of energy to be shifted to times when energy is cheapest, which will help to lower our bill,” Lack says.

Schneider Electric is also preparing a project with the City of Grenoble that will allow the benefits of such flexibility in electrical supply to be brought to the community. The municipality and the company responded to a call for projects together under France’s Investment for the Future (PIA 3) programs and have applied for the smart-city designation funded by the European Union.

Buildings such as Schneider’s flagship creations, created in perfect symbiosis with BIM models, could help create a new standard in efficient building operation and energy performance.

About the author

Maxime Thomas

Maxime Thomas is an editor for the French national and specialized press. He has also worked in radio and covers various aspects of industrial life, including digital transformation and its specific consequences for certain professions.