Is timber bamboo the future of climate-positive industrialized construction?

Timber bamboo is a renewable, carbon-sinking building material. With growing demands of the built world, it could be a game changer for global construction.

Zach Mortice

August 25, 2022 • 8 min read

Timber bamboo as a construction material is a fast-growing, renewable-resource alternative to carbon fiber.

BamCore is part of the Autodesk Foundation impact-investing program, which supports the company’s vision to encourage climate-positive building materials.

In addition to environmental benefits, BamCore’s prefabricated timber-bamboo composite saves time and money on jobsites.

To address the converging crises of climate change and rapidly growing global populations that need housing, a hardy and quick-growing grass is gaining popularity as a building material: timber bamboo. Bamboo is often undervalued as a structural building material because of its straw-like, tubular shape. But as the world keeps building, material sustainability is becoming a critical concern.

“It is projected that we will build the equivalent of a new New York City every 30 days for the next 40 years, and the built world today produces 40% of the global carbon footprint,” says Hal Hinkle, CEO of BamCore, a construction technology company that has developed a prefabricated hollow-wall solution using a timber-bamboo composite. “So how do we build that much while reducing the world’s carbon footprint?”

What is timber bamboo?

Bamboo is transformed into wood-hybrid engineered panels that are fabricated into wall sections for multifamily, single-family, and commercial buildings. By assembling parallel strips of bamboo into rigid sheets and backing them with plywood, BamCore preserves the integrity of ultrastrong bamboo fiber strands (“one of nature’s strongest cellulosic fibers,” Hinkle says), similar to carbon-fiber filaments encased in hardened resin.

What are the benefits of timber bamboo?

Unlike carbon fiber, bamboo is a renewable resource and a powerful carbon sink, sequestering five to 10 times more carbon dioxide than wood. According to Hinkle, “Timing is everything in climate change.” Bamboo is a species of grass that grows rapidly for its first eight months, with some species growing as much as 3 feet in one day. After about three years, the bamboo is fully mature and possesses its maximal mechanical strength. One of the most important attributes of bamboo is that it can be harvested every year—without killing the plant—and then stored in long-service-life products, such as buildings, making them long-term carbon sinks.

Hinkle says that to avoid accelerating climate-change feedback loops, it’s necessary to replace as many conventional construction methods with low-carbon solutions as quickly as possible. “As good as wood is, it loses the timing game,” he says. “Only bamboo can win the timing game.” BamCore has been scaling up its production capacity to beat the climate clock; its new fabrication facility is already supplying an 840,000-square-foot residential development with BamCore panels.

Shaping stronger slats with engineered bamboo

The BamCore wall system is aimed at the standard low-rise balloon-framing construction market. The wall units begin with standard lengths of bamboo stalks that are cut by suppliers in the field into thin strips called slats. These are shipped to the BamCore factory in Ocala, FL, where the slats are refined into pure rectangles that can be combined with wood into the engineered panels and wall system.

For each wall section, the BamCore Prime Wall System uses two panel runs, which are held down to the building deck using traditional methods and then joined panel-to-panel with shiplap connections. The process requires no heavy equipment and results in a near-hollow cavity, eliminating most studs, headers, and posts.

“The whole face of the wall is basically a stud you can drill into, so there is no more stud-finding for things like siding, finish moulding, and cabinetry installation,” says Zack Zimmerman, BamCore’s chief revenue officer.

Hinkle says the new fabrication facility in Florida is a “seeing-is-believing inflection point” for engineered bamboo—for contractors, framers, and other trades that will build with the new system in the field and for purchasing executives, who have to know the supply of components will be reliable. “There’s a difference between handing someone a sample and showing them a factory with produced inventory,” he says.

Getting this factory running for a relatively untested building component required some resourceful thinking. From the outset, BamCore looked to find undervalued assets it could work into production, similar to the way it found value in bamboo. Its first question was, “How can you reduce the capital expenditure required?” Hinkle says. “We did that by taking a grand plan and chunking it down into stages of implementation.”

Investing in timber-bamboo construction for the future

BamCore made tough decisions in order to stretch its limited budget as far as possible. In 2019, the company purchased a retired Georgia-Pacific factory (including the old but still-usable machinery inside), paying a fraction of what might cost $15 million–$25 million for a new engineered-wood facility. The person the company purchased the facility from, Tom Scott, became an investor in BamCore. Scott is a veteran of the engineered-wood industry and has a keen eye for used, low-cost, engineered-wood machinery that could be brought in from elsewhere in the United States and Canada and then retrofitted in-house. Scott’s company, Lewis & Clark Industrial, has helped build out facilities around the world.

Before the end of 2021, the factory will be able to churn out 100,000 panels each year; at full capacity, an expanded plant and property can produce up to 1 million panels per year. For the company’s first major project, a multifamily townhome development in Salt Lake City for Concord Homes, BamCore is supplying 50,000 panels for 340 housing units. “We’re bootstrapping our way into the big plan,” Hinkle says.

BamCore is a start-up in the Autodesk Foundation’s impact-investing program, which supports the company’s vision to bring climate-positive building materials into the built environment to tackle climate change. For Hinkle, that pitch is simple: “I consider bamboo a gift of nature that mankind has yet to fully discover.” Much of that discovery process lies in developing a mostly nonexistent supply chain. “There’s no multiparty global supply chain in timber bamboo,” he says.

Predating a more robust supply chain, early projects using BamCore showed off its range of facade and finish customization, which can incorporate paint (applied directly to the panels with no drywall needed), plaster, masonry, stucco, and siding—or charred wood.

That’s the finish Jack Becker and Andrew Linn used on the office and studio for their architecture firm, Becker Linn Design in Washington, DC. They call their office “The Grass House,” the first BamCore project on the East Coast. All but one load-bearing wall in the structure is made from BamCore. The exterior is a richly textured, uniformly charred cedar and cypress. Inside, the duo painted with fire, using a handheld torch to “experiment with ways of highlighting the grain with the flame,” Becker says. The result covers the Douglas fir veneer with a feathered, tiger-stripe pattern of hypnotic whorls.

Prefab with timber bamboo in production saves time and money

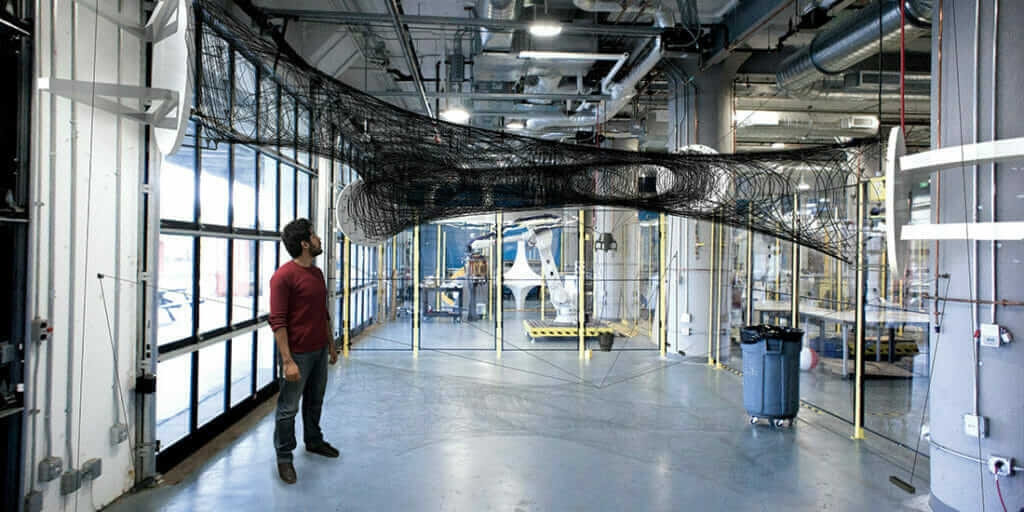

To ease its prefab system into building sites, BamCore is developing design software that consolidates revisions from contractors and building trades within a cloud-based interactive 3D model. First, BamCore receives CAD files from the architect and translates each planar section into panelized schematics. Using the Autodesk Forge platform, this 3D model is shared with the trades so they can design in mechanical, engineering, and plumbing (MEP) features before fabrication. Components roll off the factory line with the locations for plumbing and electrical services and nail-connection points printed on the panels in designated colors.

This method offers logistical and labor advantages. With fewer internal elements in the wall sections and MEP routes preplanned, things come together quickly and don’t need to be revised. For an 1,800-square-foot space, just the lack of studs can save a framer five days of labor. “It’s tilting it up and nailing it together,” Becker says, adding that the system scales easily once the framing team becomes familiar with the process.

On larger multifamily housing projects, material efficiencies add to labor efficiencies. First, because there is minimal cutting and sawing, jobsite waste is significantly reduced. Second, Sheetrock and sound-attenuation systems can be reduced or eliminated, producing additional material savings.

The fabrication and application of engineered hybrid-bamboo products stand apart from more familiar versions of engineered wood and mass timber. But BamCore is also looking for ways to turn bamboo into “something that we can bring into a hybrid relationship with CLT,” Hinkle says.

Research suggests a hybrid bamboo and cross-laminated timber (CLT) system can be stronger, thinner, or both. The core point is: “The time is now for multiple timber-bamboo solutions to play a role in lowering the carbon, cost, and labor of the built environment,” Hinkle says. “We view bamboo as a gift of nature that might be our most underutilized natural material when it comes to addressing climate change and our need to build globally.”

This article has been updated. It was originally published in December 2020.

About the author

Zach Mortice

Zach Mortice is an architectural journalist based in Chicago.