& Construction

Integrated BIM tools, including Revit, AutoCAD, and Civil 3D

& Manufacturing

Professional CAD/CAM tools built on Inventor and AutoCAD

8 min read

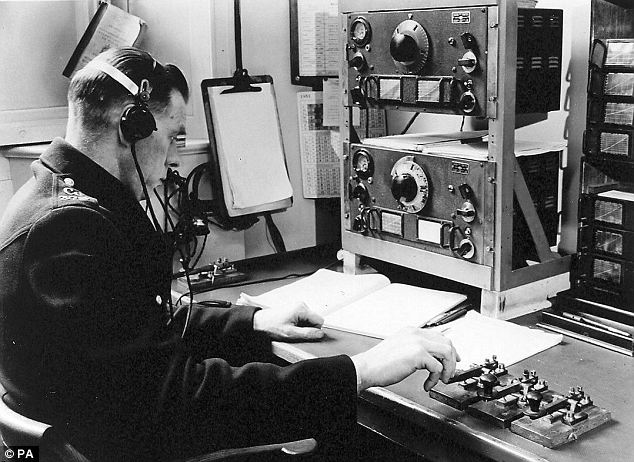

It’s a cold, blistering night in the middle of the Atlantic. You’ve been contracted by the United Fruit Company on a shipping barge to haul tons of produce halfway around the world. At the helm of your ship is a single wireless radio, one of the first to be installed for maritime operations. The only sounds out of it are the slow, steady boops and beeps of Morse Code, but then something interesting happens.

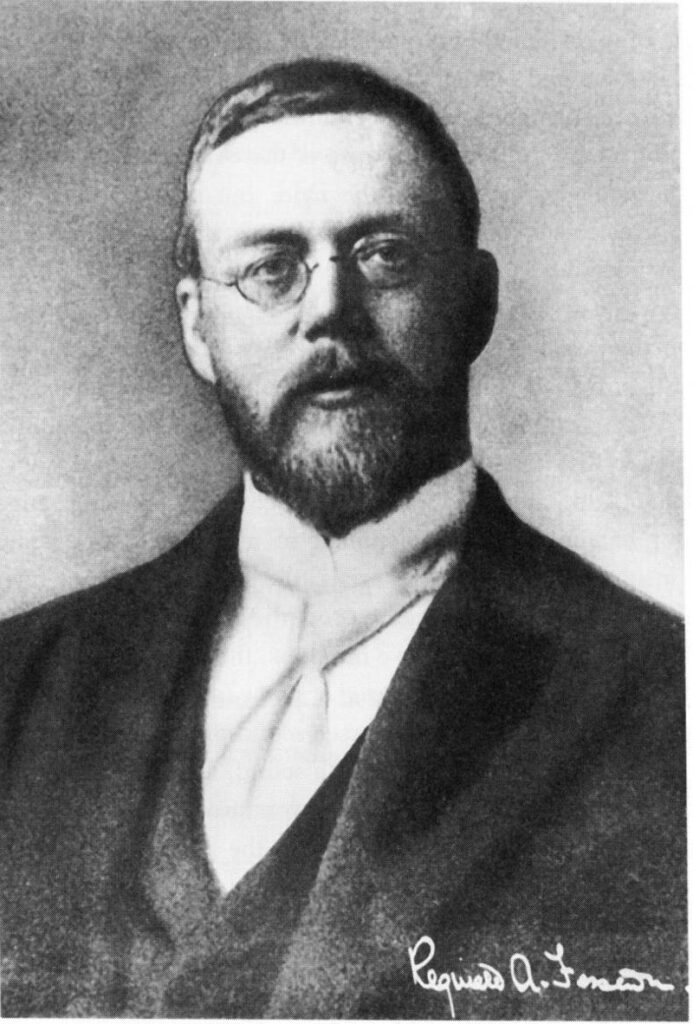

Your ship receives a signal in Morse Code, “Be prepared for something of great interest to follow.” You wait for the next series of beeps, but instead of a beep, you hear the first human voice transmitted from hundreds of miles away. You’re literally hearing history being made. Is this an angel speaking to you from above? “O Holy Night” begins its soft melody from a violin nowhere in sight. This isn’t an angel playing, it’s the Father of Radio at work, Reginald Fessenden!

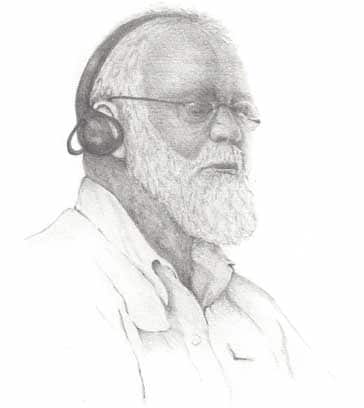

Many inventors are lost through the sands of time, and Reginald is no exception. Intensely criticized and mocked for his theories, and forced to fight for his inventions, this man helped pave the way for our wireless technologies today. He deserves recognition.

The Father of Radio was born on October 6, 1866, in Quebec, Canada. His mother was a minister in the Church of England and Reginald was expected to walk in her footsteps as a church minister or teacher. Fessenden had other ideas:

“When I closed my eyes and dreamed, I saw an invention that could send voices around the world without using wires or cables.”

His mother said there was no future for such dreams. Boy was she wrong.

Reginald was a quick study but never completed his high school studies. Instead, he chose to move to New York in 1886 with the hope of gaining employment with the Edison company. Edison eventually took Reginald on after many denials and sent the man to work laying underground electrical cables in the heart of the city. Fessenden’s work ethic and brilliance soon shone through, and he was promoted in 1886 as Edison’s Head Chemist in New Jersey. It was here that Reginald’s natural aptitude for science and mathematics started to flourish.

For the next four years, Reginald honed his skills in the sciences. Then Edison’s company hit a snag of financial issues in 1890 and had to lay off some of its staff. Fessenden was on that list. Thankfully, Reginald’s skills were well known by this time, and he was picked up to work for George Westinghouse. After working at Westinghouse, Reginald became head of the newly created electrical engineering department at the University of Pennsylvania. Again, without finishing his high school education.

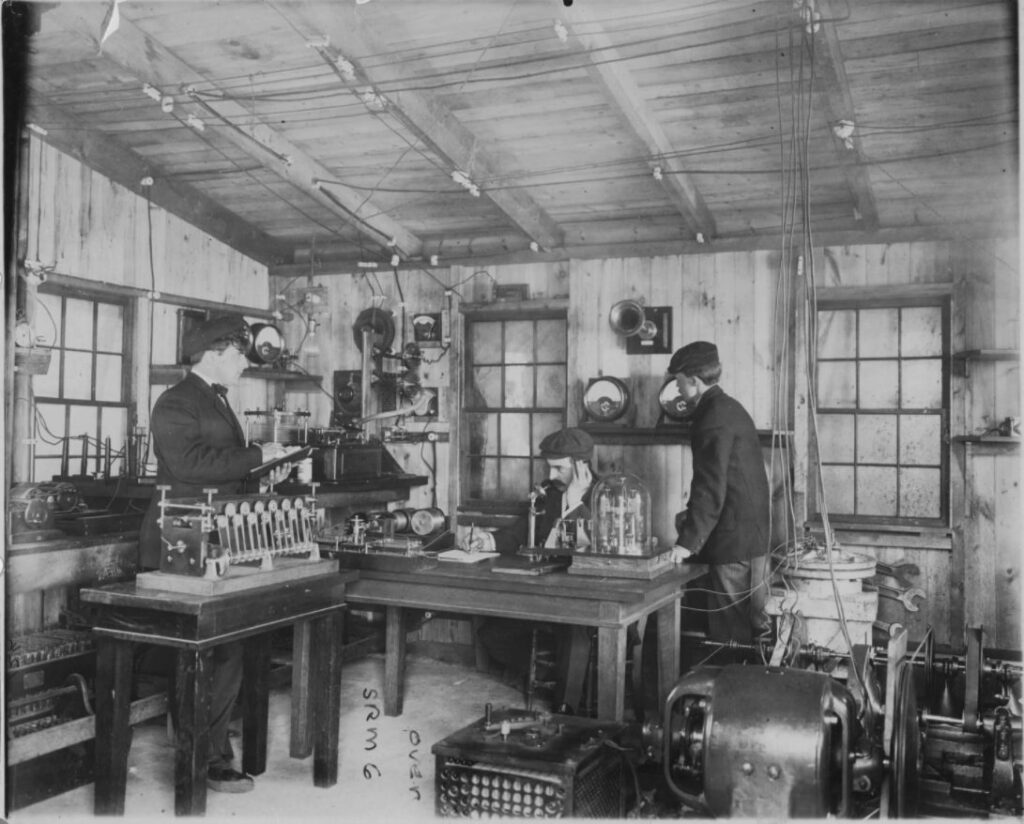

During his time at university, Westinghouse agreed to make instruments and machines for Reginald to test his wireless technology theories, and Fessenden remained available to Westinghouse for research. This provided the perfect opportunity for Fessenden to work on his studies of electromagnetic waves as the world was in a mad dash to improve the Morse Telegraph System.

It was during this period that Fessenden and his assistant, Mr. Kitner, made a discovery. While tinkering with a transmitter and receiver, Kitner accidentally jammed one of the Morse code keys. The produced sound wailed through the receiver to Reginald in the other room. Fessenden realized that if this howl could be carried wirelessly from transmitter to receiver, couldn’t the same be said for human voices? What Reginald needed was a way to produce high frequency waves which could carry these sounds.

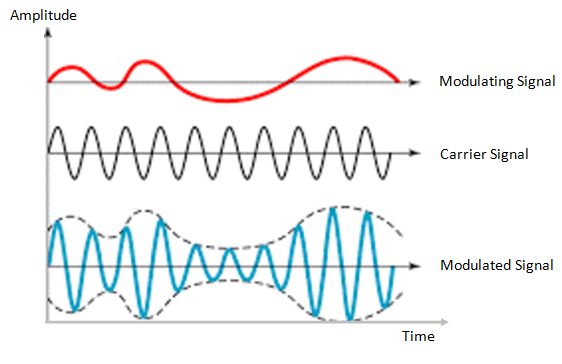

Fessenden theorized that you could broadcast information embedded in a high frequency wave, and a receiver could then isolate the broadcast from the carrier wave, leaving only the intended sound. All he was lacking was the high frequency electromagnetic waves to make this happen. Reginald had developed the theory for amplitude modulation.

Reginald realized that he would need more money than his university salary offered to build a generator that could produce high frequency electromagnetic waves. He decided to leave his post at the University of Pennsylvania and pitched the idea of radiotelegraph equipment to the United States Weather Bureau for improved weather forecasting. With the job won, Fessenden could now develop transmitters and receivers while also working on his theories with the U.S. Weather Bureau’s generators.

It was at Fessenden’s new lab at Cobb Island, Maryland, where he started to experiment with wireless transmissions to a receiving station 50 miles away in Arlington, Virginia. Here, Reginald and his assistant took advantage of a new generator to perfect the transmission of Morse Code transmissions. On December 23, Reginald added a microphone to his setup and telegraphed “One, two, three, four. Is it snowing where you are Mr. Thiessen? If so telegraph back and let me know.” The message was received, and Thiessen telegraphed back! Fessenden hurried to write at his desk about the event:

“This afternoon here at Cobb Island, intelligible speech by electromagnetic waves has for the first time in World’s History been transmitted.”

For context, this happened a year before Marconi transmitted Morse Code from England to Signal Hill in Newfoundland. Reginald was way ahead of his time.

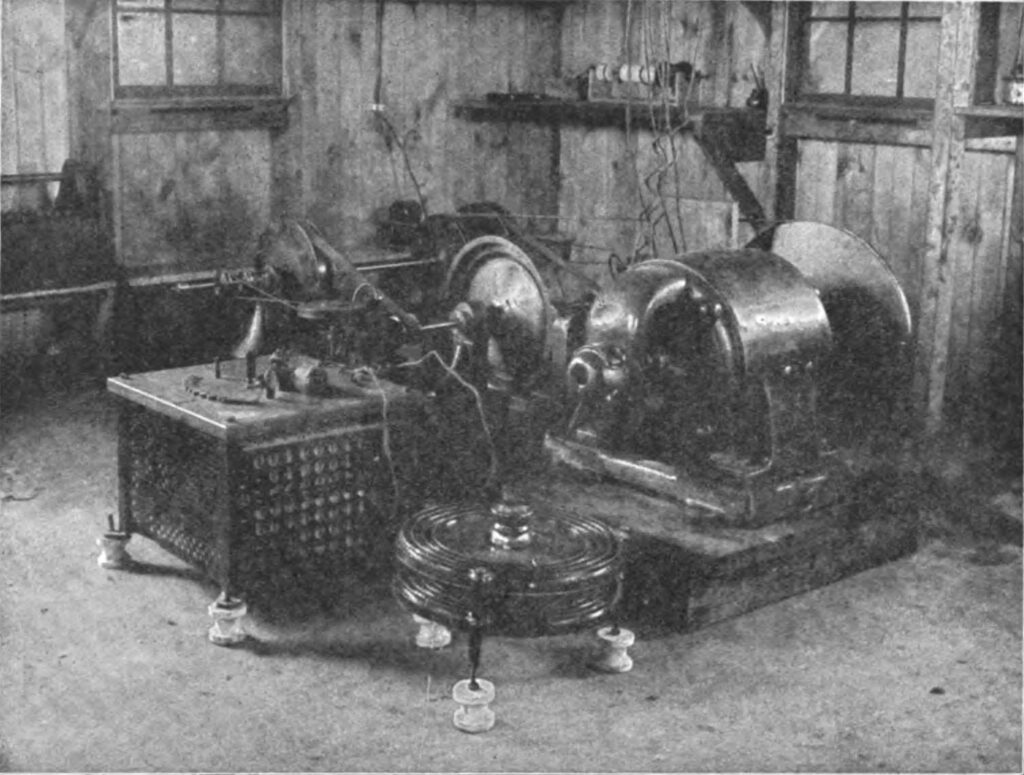

Reginald worked to improve the system he had created over the next two years. He made major advances in receiver designs and developed two new detectors, a barretter detector, and an electrolytic detector. The generator was modulated by placing a carbon microphone in the antenna lead, and the message was sent using a spark gap transmitter. While this did transmit a message, the receiver heard the hiss of the spark’s arc.

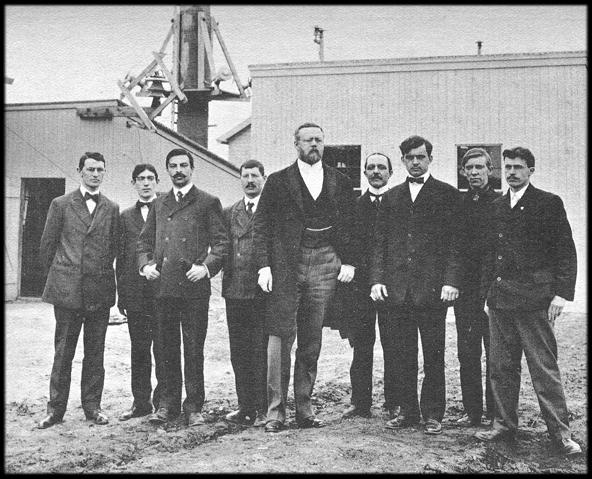

The work that Reginald accomplished here didn’t go unnoticed. Two wealthy investors by the name of Hay Walker Jr. and Thomas Given would approach Fessenden to finance his dreams of wireless radio communications. The trio formed a new company called National Electrical Signalling. It was here that Reginald would finally bring O Holy Night to the masses.

The goal of the new company was to establish a two-way transatlantic communication system between a station in Brant Rock, USA, and another in Machrihanish, Scotland. While Marconi had successfully completed the first transatlantic transmission in 1901, it was only possible in one direction.

It was during this time that the Father of Radio dove into the development of a high frequency alternator to power his needed electromagnetic waves. He had an alternator delivered in 1903, but it could only operate at 10 kHz. Another alternator was produced in 1905 but again could not operate above 10 kHz. Instead of wasting more money, Reginald decided to build his own alternator using parts from the existing devices. His high frequency alternator was able to produce his needed 75 kHz frequencies with 500 watts of power output. This device, completed in 1906, would allow him to transmit the continuous electromagnetic signals that his system required.

Unfortunately for Reginald, his plans came crashing down. Development work on the Scotland tower literally collapsed on December 6, 1906, while the construction crew was working on the steel guy ropes. Both Walker Jr. and Given decided that rebuilding the station was just too costly. The project was abandoned.

Instead of scrapping all of his efforts, Reginald had an idea. He had an alternator to produce his continuous waves; now he just needed a set of receivers to see if his message could be received. On December 24, 1906, at 9 PM EST, Reginald transmitted the first human voice over the radio from Brant Rock, Massachusetts to ships in the Atlantic owned by the United Fruit Company.

Reginald began his broadcast with a recording of Handel’s “Largo,” and then played the Christmas classic “O Holy Night” on his violin. He concluded the broadcast with a famous passage from the Bible, Luke 2:14, “Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests.” Then he bid his audience a good night, asking those who heard the broadcast to write to him. The response was overwhelming. The broadcast was heard by all of those who tuned in, and Reginald Fessenden was officially the first human voice ever heard over the radio.

Reginald gave the world one of the greatest gifts ever on that Christmas Eve. Human voices could now be transmitted over vast distances with wireless radio. As we’ve seen today, this has transformed entire industries and methods of communication. With his work complete, Fessenden waited for the money to start rolling in, but a different story started to unfold.

His wealthy business partners, Mr. Walker Jr. and Mr. Given, ended up selling Reginald’s patents to American companies like RCA. The Father of Radio spent a good portion of his later life fighting for recognition and revenue from his inventions that were making other companies rich. Until 2008, Reginald wasn’t even listed in the Encyclopedia of Canada. The only mention of the man was under his mother, Clementina. Even today his list of achievements spans a measly two paragraphs on Historica Canada’s website.

Despite the way history has tried to forget such a brilliant man, his works live on today. Reginald pushed radio and wireless technology into new territory that no one could rightly see. Without his insight and intuitive understanding of electromagnetic waves, we might still be relying on Morse Code or some other primitive communications technology today.

Reginald Fessenden was a brilliant inventor and deserves more recognition than he was given. He held over 250 patents without ever finishing his high school education! This man needs to be on the front pages of our history books, not forgotten. It’s inventors and engineers like Reginald that truly make this world a better place.

Rest in peace, Reginald. Your work is still alive all around us.

Got an invention you want to bring to life? Design it now in Autodesk EAGLE for free!

By clicking subscribe, I agree to receive the Fusion newsletter and acknowledge the Autodesk Privacy Statement.

Success!

May we collect and use your data?

Learn more about the Third Party Services we use and our Privacy Statement.May we collect and use your data to tailor your experience?

Explore the benefits of a customized experience by managing your privacy settings for this site or visit our Privacy Statement to learn more about your options.