Both fandom and professional design have a rich history of taking characters or creatures that exist only in digital form and building them in the real world.

Makeup artist Holly Conrad stopped 2011’s Comic Con in its tracks with her costumes based on the game Mass Effect, with incredibly detailed creature makeup. For the cinema release of Pixar’s Wall.E, LA studio JJ&A created a fully articulated cardboard model of the titular robot for the cinema standees that was sent to movie theatres all over the world.

Early on during such projects, designers or engineers invariably come up against properties of the real world such as gravity, mass, torque, and tension—forces CGI animators and game designers can conveniently ignore.

British creative engineering consultancy Robo Challenge faced the same puzzles when Microsoft asked it to build Mack, the dogbot character from the XBox game ReCore.

Microsoft wanted to publicize the ReCore launch in a unique way by introducing Mack in the real world to sit, stand, and walk like he does in the game.

As Robo Challenge co-founder James Cooper explains, the company (which he runs along with his brother and father) enthusiastically steeled itself for the inevitable point when reality would set in.

“We thought it looked like such a cool project,” Cooper says. “Then [Microsoft] gave us the dimensions, and we thought, ‘Ah, there are actually no off-the-shelf motors, gearboxes, or actuators that would make his legs move, lift him, or stand him.’”

Ordinarily, it wouldn’t have been a big problem to build the electronic and skeletal inner structure to support Mack or enable his movement, but it would have meant different parts from those of his in-game namesake—and that would have defeat the purpose.

The weight/power arms race

There’s a paradoxical principle in robotics called the mass differential: Every autonomous robot needs an onboard power source, but every unit of weight it needs to carry (in the form of a battery,  for example) adds to the weight, requiring more power in turn and so on.

for example) adds to the weight, requiring more power in turn and so on.

In a way, it made designing Mack twice the engineering conundrum. You can see just by glancing at his lower legs how little space there is for gears and motors, and Cooper and the team came extremely close to the limits of what the physics of the real world could do.

“The last little joint [in the hind legs] has to take just as much load as any of the other joints but it’s actually the smallest area,” he says. “To get a motor in there, we only had a couple of inches of clearance just to get the wires up through his legs. There are six electric motors in his rear legs and that’s quite a small space to fit everything in.”

The team plasma-cut Mack’s skeleton from steel, including as many holes and pockets as they could to remove weight while maintaining the robustness. Then, they 3D printed bespoke extensions within connected small motors and gears, driving Mack while keeping out of sight, and the exterior panels that would be visible. Although Mack would look exactly like his digital self, he’d have a much stronger internal structure.

When Microsoft first approached Robo Challenge, it hadn’t released any images or designs—the company told James and the team he’d be “normal dog size.” When Mack turned out to be close to four feet tall, Robo Challenge knew the weight would be considerable (the end product was around 25kg/55lb), which meant a lot of brainstorming to think up the musculature to hold him upright.

Best (maybe worst) of all? They had a month to make Mack in his entirety.

Blueprints for the real world

To get started, the Robo Challenge team had only YouTube videos, the game itself, and some high-resolution press graphics of the dogbot. Together, they provided the reference for the way Mack walked, the way his head moved, the placement of his eyes and ears, and every other detail.

walked, the way his head moved, the placement of his eyes and ears, and every other detail.

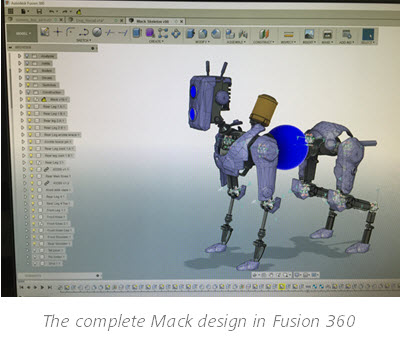

The first step was to fire up Fusion 360 and dive right in. The game version of Mack naturally isn’t too concerned with what’s under his skin, so the inner workings had to be designed from scratch—all while keeping in mind that whichever bits might peek out from under the exoskeleton had to match those of the in-game character exactly.

To James’s brother and cofounder, Grant, the new paradigm in 3D design that Fusion 360 represented removed a lot of old pain points, despite any learning curve. “Because we were working on such a short time scale, we could have three people designing at exactly the same time on the same model,” he says. “All of us working on it would instantly get those updates and carry on designing around what someone else was doing at the same time.”

If someone was designing a part that the team figured out didn’t work so well, the built-in version control offered the ability to step back and start again from the last usable step.

It called for a parallel process of designing pieces while running them off the 3D printer to test at the same time. Cooper estimates the development and delivery period contained about 1,000 hours of 3D printing.

“A team of us were designing in Fusion 360 whilst the other guys were getting bits off the printers and preparing them and making the skeleton,” he says. “It was very much teams running alongside each other until the end. There wasn’t the classic stage of design.”

The real test

So after all that development and prototyping and all those late nights, how did Mack perform when transposed to planet Earth? “We had some struggles with the rear legs, but we ended up installing a special chip that controlled the legs, making them operate smoothly and work the way they would in a real dog,” Cooper says. “Getting them to move fluidly was a decent challenge, but it went amazingly.”

When both Robo Challenge and Microsoft realized Mack looked like he’d leaped straight out of the game, they knew they’d done it.