Nicolas Huchet never intended to become a designer, much less an organizer of design projects for people with disabilities. But then life events—including the loss of his hand and his exposure to 3D design and printing tools—changed all that.

A Maker Project for People with Disabilities in France

Today Huchet, who’s in his early thirties, heads up a nonprofit organization called MyHumanKit in the French city of Rennes. While his technical focus is on developing the Bionicohand prosthesis, his deeper interest is in the social aspect of the work.

While the technology the organization uses is great for making things, that’s not the real point. “The 3D printer is cool,” he says, “but we don’t really care about the 3D printer [in itself]. We’re more interested in the fact that the 3D printer will attract people”

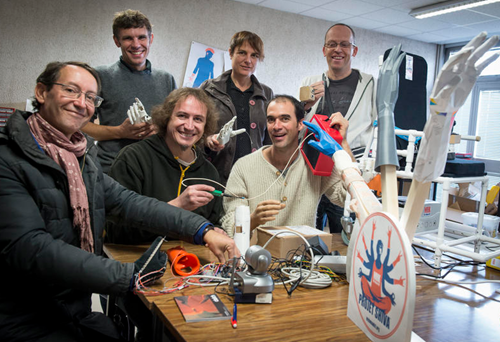

The group has begun hosting maker events that bring engineers and designers from companies like Airbus, BNP, Safran, Cap GeminiDassault, and Renault Sogetti, Thales, together with disabled people and friends and families. At the events, there’s a free exchange of ideas among professionals, hobbyists, and end users prototyping about products like the Bionicohand, open source wheelchairs or 3D printers hacked into braille machines.

Improving Life for Disabled People through 3D Design

Huchet emphasizes the need to involve disabled people in the design process. “We think it’s important to remind the engineers that, in the end, what they do is supposed to be used by people,” he says. “So it’s important to work together.” He thinks that’s even more important when end users are disabled, simply because life is harder for them.

He speaks from experience. Fifteen years ago, when he was an 18-year-old studying industrial design, Huchet served an apprenticeship as an industrial worker. One morning, his hand was caught and crushed in a hydraulic press he was operating. After the accident, he didn’t want to work in that field anymore. He says that, for a long time, “everything was dark” for him.

For Huchet, designing and making his own prosthetic technology is not only practical, but also an empowering form of psychotherapy. He says he used to succumb to persistent thoughts that ”life isn’t fair,” or that he was a victim. By contrast, learning 3D design has allowed him to think differently about “turning your limitation into a motivation.”

Huchet jokes that the money he spends on things like Arduino cards is money he doesn’t need to pay to a psychologist. And he finds that when he gets absorbed in his work, suddenly he doesn’t need to know anymore why his accident happened. “The questions disappear by themselves.”

Using Fusion 360 to Build a Better Artificial Hand

That sense of empowerment has driven Huchet’s work on the Bionicohand. A few years ago, he was looking at ways to raise the money for a sophisticated myoelectric hand. Now he’s not, because he’s made his own. And whereas the myoelectric model might have cost €50,000, his version has required less than €1,000 for parts and 3D printing, plus his own time.

He created the first iteration of his bionic hand in 2013 in the LabFab in Rennes. Later, he was able to spend three months at FabLab Berlin, where he first encountered Fusion 360. Now he and his colleagues use the software regularly to refine prototypes and design new devices.

In the case of the Bionicohand, they have been able to tackle one of the trickiest parts of fitting prosthetics by taking a 3D scan of Huchet’s residual limb, importing it into Fusion 360, and then using that to model the socket for the prosthesis — “the [one] thing that must be customized,” as Huchet explains.

He adds that he appreciates the accessibility of Fusion 360. It’s become a regular part of the workflow for the MyHumanKit team, and they particularly love that Fusion 360 files live on the cloud, making them easy to share with anyone. That’s particularly useful given that the organization is committed to an open source approach with their designs.

Now Huchet is using Fusion 360 to improve the mechanical design of the hand’s fingers and thumb, and to refine his designs for the PCBs and other components inside the prosthesis. Over time, he and his colleagues want to experiment with different materials as well as 3D-printed adaptations of prosthetics that are more useful for certain sports and other activities.

Making a Difference for People with Disabilities

Thanks to his experiences in open source design, Huchet says, his life is now going in a direction he likes. Today, MyHumanKit has a team of four full-time employees, along with a community of dozens of heavily involved volunteers. They’re excited that they now get messages from people around the world who are using their designs. My Human Kit opened its own Fablab called Humanlab in which people can come to learn “how to fit themselves”.

Huchet says the group wants to get people thinking not just about specific devices, but more generally about how technology and disability relate to each other. That approach has helped expand the thinking of both technical contributors and end users.

In everything they do, Huchet says, “we want disabled people to be the center of gravity of the project.” He and his MyHumanKit colleagues also want to be sure never to forget why they do what they do.

“The most important part is the human part, which is being involved in healing yourself.”