Warning: Content May Be Offensive or Disturbing to Some Audiences.

Rebel With a Cause: Bob Widlar – Engineer, Artist, Prankster, and Legend

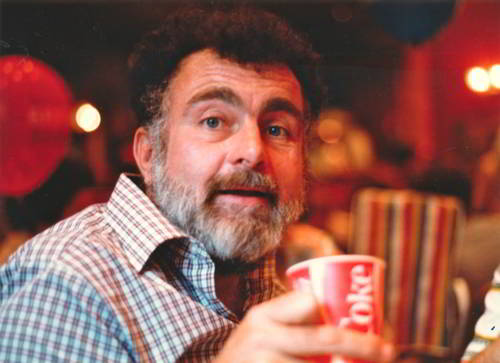

Bob Widlar wasn’t just a good hardware engineer; he was a legendary one. Even today, he’s considered one of the most famous hardware engineers to ever live. Not just for his genius designs, but for his rebellious and entrepreneurial personality that seemed to exist in a universe of its own. For over a decade, Bob ruled the world of Analog IC design with famous designs like uA702, the first linear IC operational amplifier. Or LM109, the first high-power voltage regulator. We’re not just here to rattle off all of Bob’s landmark achievements though. We think Widlar would appreciate a more well-rounded look at his life. From integrated circuits to sheep and more, this is the story of Bob Widlar as we know it.

Bob Wasn’t Just an Engineer

Bo Lojek, the author of History of Semiconductor Engineering, described Bob as, “more artist than engineer…in the environment where Human Relations Departments define what engineers can and cannot comment about, it is very unlikely that we will see his kind again.”

“more artist than engineer…in the environment where Human Relations Departments define what engineers can and cannot comment about, it is very unlikely that we will see his kind again.”

Bob is the kind of engineer that I always pictured in my head, wild-eyed in both mind and actions, but a true genius at heart. No, he didn’t sport a Gandalf-like beard from the likes of Bob Pease, but Bob’s circuits seemed to manifest from some other dimension of reality and spontaneous creativity.

The artistic and bohemian side of Bob’s personality fit in with the times. In the late 1960s and 70s, the semiconductor industry was like a scene from a Wild West movie. Bars were packed day and night, circuit innovations were pouring out like a beautiful waterfall, and in the center of all that change and chaos was Bob.

By all means, Bob enjoyed his alcohol. There are stories floating around of Bob refusing to give a speech until he was provided his allotment of scotch or wine. But compared to the wild times of the day, the Bob we envision now might not have been all that crazy when you look at the environment he worked in.

As the History of Semiconductor Engineering describes, “Bob was a fiercely independent individual, very happy to be by himself, and he did everything in a stunning way, which was absolutely natural to him, but completely weird to so-called ‘normal people’.”

In short, Bob didn’t really give a damn about what others thought about him. I suppose when you’re the one shaping an entire industry, that mentality is just a given.

Bob’s Passion for Electronics Started Early

It’s challenging to dig up any personal details from Bob’s early life, and he was reported to rarely speak of his early years. What we do know just scratches the surface, but shows that electronics played a huge role in Bob’s early life.

Robert Widlar was born on November 30, 1937, in Cleveland to mother Mary Vithous and father Walter J. Widlar. His father was a self-taught radio engineer who worked at a local radio station. He would leave behind a legacy of designing ultra-high frequency transmitters.

Since his birth, electronics were all around Bob, and so he followed what his environment presented to him and pursued a passion for engineering. At the age of 15, Bob was featured in a local newspaper as an electronics designer who repaired radio and TV sets. Bob also reportedly enjoyed playing radio pranks on the Cleveland police, but details of those pranks are scarce.

Bob’s budding passion for electronics fully matured when he joined the United States Air Force in 1958. Here Bob was responsible for instructing his fellow servicemen in electronic equipment. This was also the time when he wrote his first book, Introduction to Semiconductor Devices

What’s interesting to note is that some sources say Bob’s “liberal mind” wasn’t a good match for the military environment. However, one of his yearly Air Force performance reviews tells a different story. Of first interest is a review of Bob’s strengths, where his superiors explicitly noted his superior electronics and communication skills:

“A/2C Widlar is perhaps the outstanding electronics technician assigned to Course ABR33130. His background in the field of electronics as a civilian and his present endeavours in off duty educational pursuits serve to put him “head and shoulders” above the average technicians. He demonstrates a willingness to assist his fellow instructors, who looks to him for guidance on complex electronics problems. Airman Widlar is not satisfied with mediocrity in his efforts and constantly strives for perfection. He has an above average ability to use clear concise words to express himself.”

We then get to the recommended areas of improvement for Airman Widlar. This part starts to draw connections to his later charged personality and depicts a man simply growing into his own skin and maturing:

“Airman Widlar, in the past, has tended to dramatize his frustrations at inefficiencies that exist, to a point that he creates an impression of immaturity. He has improved greatly in this area, toning down his approach to problems, and has evidenced a willingness to accept that which he cannot control. No further recurrence of this comment are anticipated.”

For reasons largely unknown, Bob chose to end his Air Force service in 1961. From there, we find Bob joining the Ball Brothers Research Corporation in Boulder, Colorado where he developed analog and digital equipment for NASA. It was also during this time that Bob completed his studies at the University of Colorado, graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering in 1963.

Bob Shapes an Industry Around His Designs

It’s in the 1960s and 1970s where Bob’s genius and renown come into full swing. We won’t bother rattling off all of Bob’s great achievements, as other articles have already done that justice. However, we will mention a couple that deserves to be mentioned over and over again:

1964

Bob catapults the semiconductor industry into a $10 billion success thanks to his LM101 operational amplifier design. During this time Bob also created the building blocks for linear IC design documented in what is now the Widlar current source, Widlar bandgap voltage reference, and the Widlar output stage. Without these contributions, our progress in IC development would not be where it is today.

1967

Bob releases his design for the industry’s first high-power voltage regulator, the LM109, with a twist. During this period there was a debate about whether it was even possible to build a high-power regulator on one chip. To settle the matter, Bob wrote a letter to several magazines which stated that it was simply impossible to produce this design, with plenty of facts and figures to justify killing the effort.

Bob was already an engineering legend by this time, so his letter held weight, and the issue seemed to be settled. However, cut to two months later and Bob introduces his design for the LM109, with all of the features he said was impossible in his letter. Widlar pulled a fast one on the industry and profited greatly. Classic Bob.

It was during Bob’s employment at Fairchild Semiconductor that he released several other landmark designs. We have uA709, a high-performance opamp, which improved on the original design of uA702 and became a flagship product of Fairchild for years. During this time Bob also released his design for the first integrated voltage regulator, uA723.

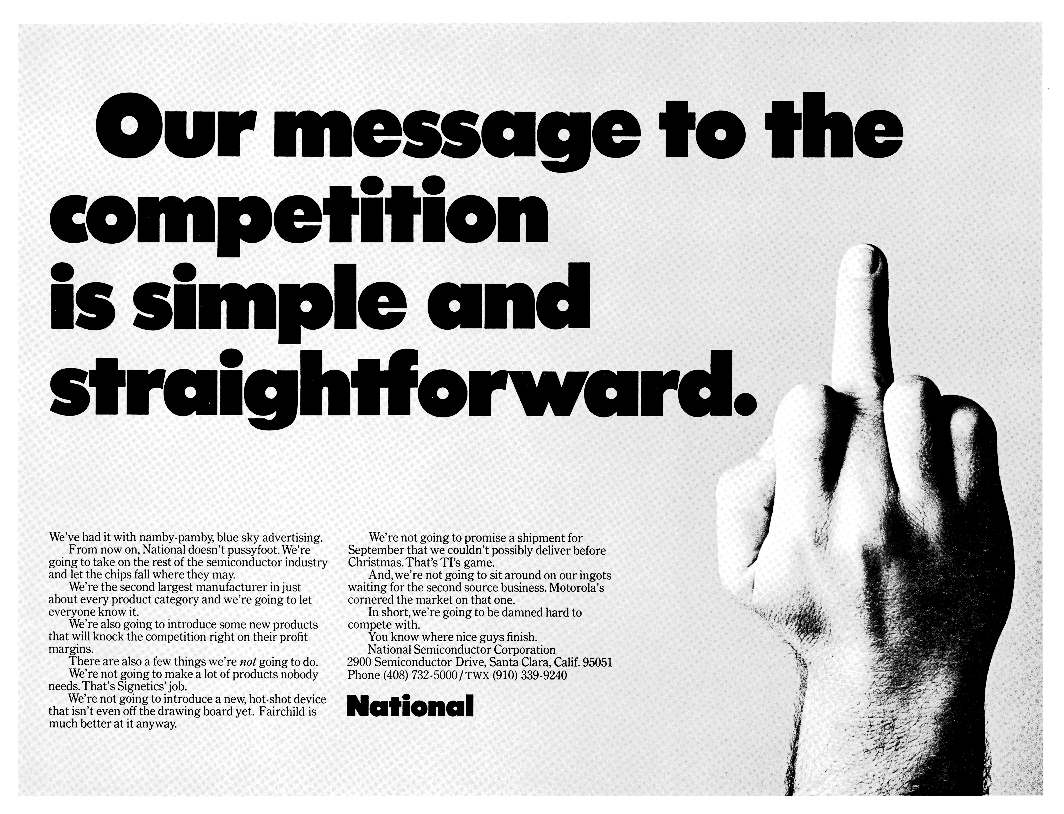

Bob Shapes an Industry Around His Personality

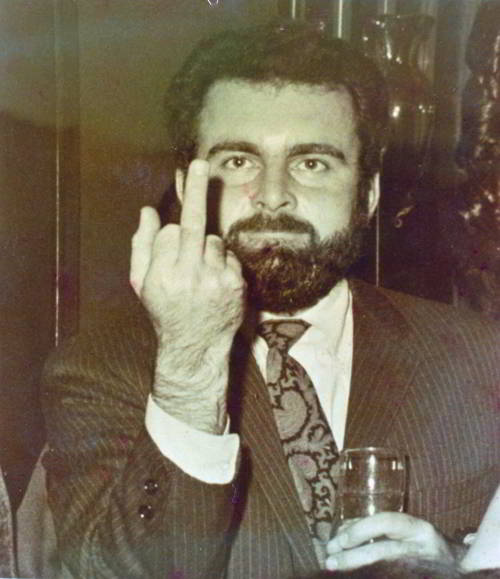

Bob wasn’t just a genius designer; he also embodied a personality that gave a characteristic Widlar Salute to the rest of the semiconductor industry.

Bob’s wild personality came during a time in Silicon Valley where counter-culture was all the rage, and Widlar just happened to be in the right place at the right time with his rebellious, entrepreneurial spirit.

When you strip away the attitude, you get a Widlar that cared deeply about the designs he created. At National Semiconductor Bob worked directly with his customers and even wrote his own app notes and data sheets. According to Bob, if you weren’t “designing for minimum phone calls,” then you were doing something wrong.

Bob’s unique designs and ‘no-bull’ attitude propelled him through a lightning-like career of success and fortune. He entered Fairchild in the 60s claiming that analog was nonsense, only to leave the company years down the road positioning Fairchild as a leader in linear integrated circuits. Bob later moved on to Molectro, owned by National Semiconductor, where he transformed the parent company into an analog design giant.

At the age of 33, Bob ended his career, cashing out his stock options from National Semiconductor to retire in Mexico. Bob’s creative brilliance soon remerged when he became a contractor for National Semiconductor in the 1980s. It was in the following years where he designed a number of advanced linear integrated circuits, including the first ultra-low voltage operational amplifier, LM10.

Bob’s Love for Pranks and Antics

While Bob was known as a genius engineer and entrepreneurial rebel, no story is complete without recounting a few of Bob’s legendary pranks. Throughout his years of engineering, Bob lived as a free-thinking prankster that was a nightmare for HR departments.

Bob’s feverish personality and humor inspired other analog engineers like Bob Pease and Jim Williams to keep his spirit alive even after his passing. Below you’ll find three of our most favorite pranks, and antics carried out during Bob’s career, but these are by no means exhaustive. Enjoy them in writing, because you’ll never see this kind of stuff pulled in today’s sterile corporate environments.

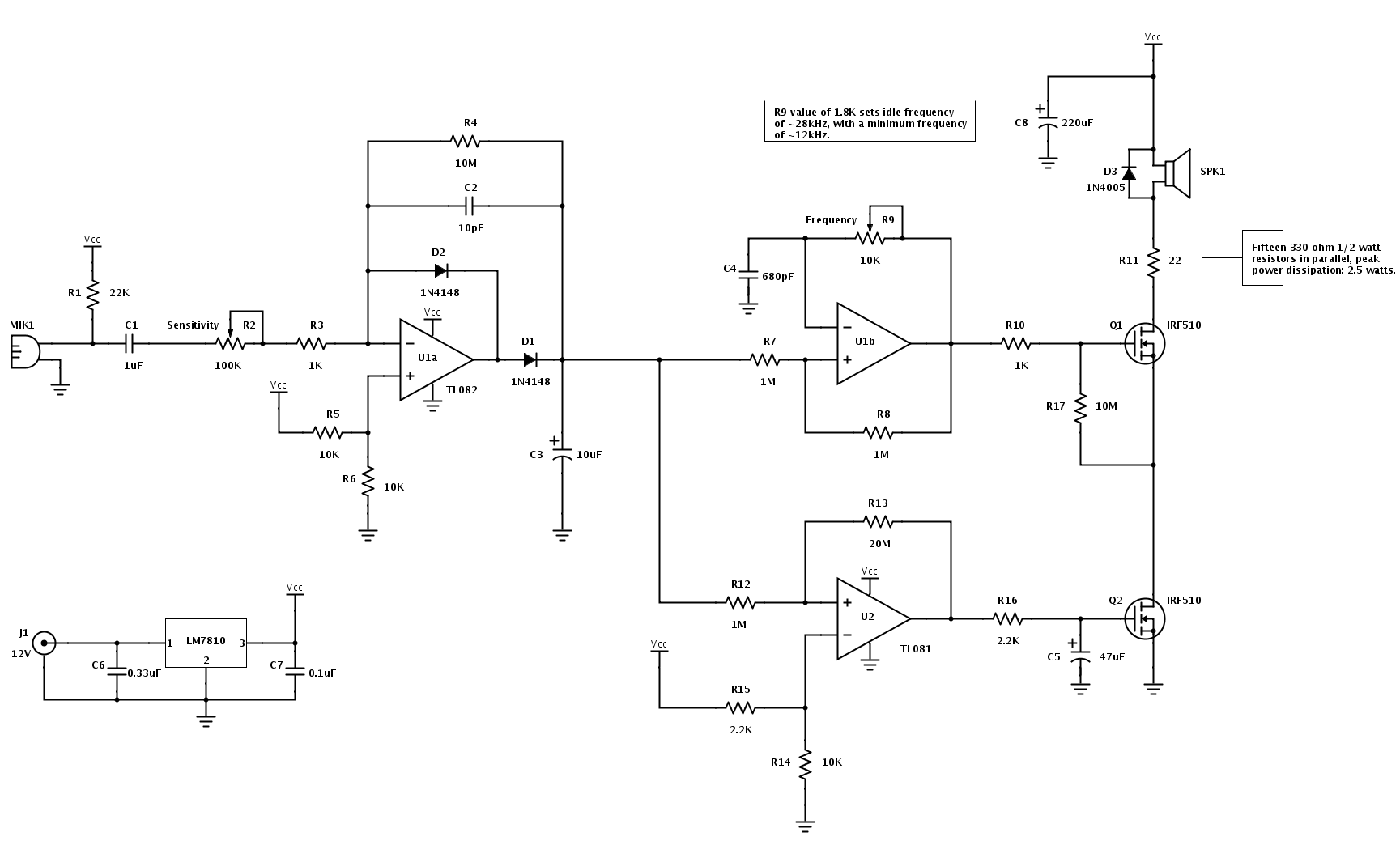

The Hassler Circuit

Widlar was a soft-spoken man and didn’t care for loud noises in his office. His solution? The Hassler Circuit. When someone came into Bob’s office to hassle him and started talking loudly, the device would detect the audio, convert it into a high frequency, and playback the converted sound.

For the visitor, the louder they talked, the louder the whining pitch from the Hassler Circuit would get. Visitors would notice this strange ringing, stop talking, and suddenly the sound disappeared. Lesson learned.

Borrowing Sheep for Lawn Trimming

In the 1980s National Semiconductor announced that it was trimming down on lawn maintenance to save money. Bob’s response? He bought (some stories say he borrowed) a sheep, packed it into the back of his Mercedes-Benz convertible, and brought it to the front lawn of National’s office. Instant grass cutting. Twenty minutes later a news report from San Jose Mercury News strolls by to take pictures of the event, and the story makes headlines. It also pissed off Bob’s employer in the process.

Widlarizing Faulty Components

Bob might have been a soft-spoken man, but he wasn’t opposed to making noise when frustration warranted it. There were times when Bob would waste an entire day on a circuit that didn’t work because of a faulty component. To make sure this component never terrorized another circuit, Bob would take the part over to an anvil in the office and beat it senseless with a hammer until it resembled dust. Widlarizing bad parts became a legend.

Keeping Bob’s Legacy Alive

Bob Widlar left us early at the age of 53 when he died of a heart attack while jogging in Puerto Vallarta. During his later years, Bob was into fitness as he curbed his alcohol habit. Some say that Bob died drunk, while others closest to the situation say otherwise, which might have amazed some of his colleagues.

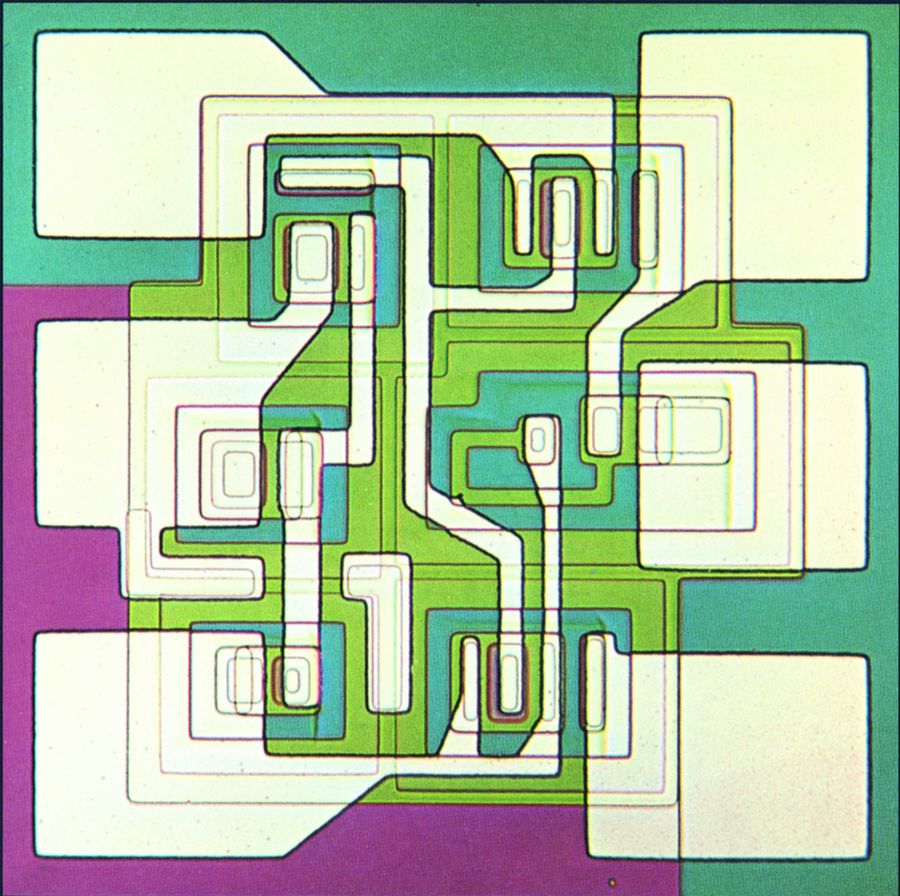

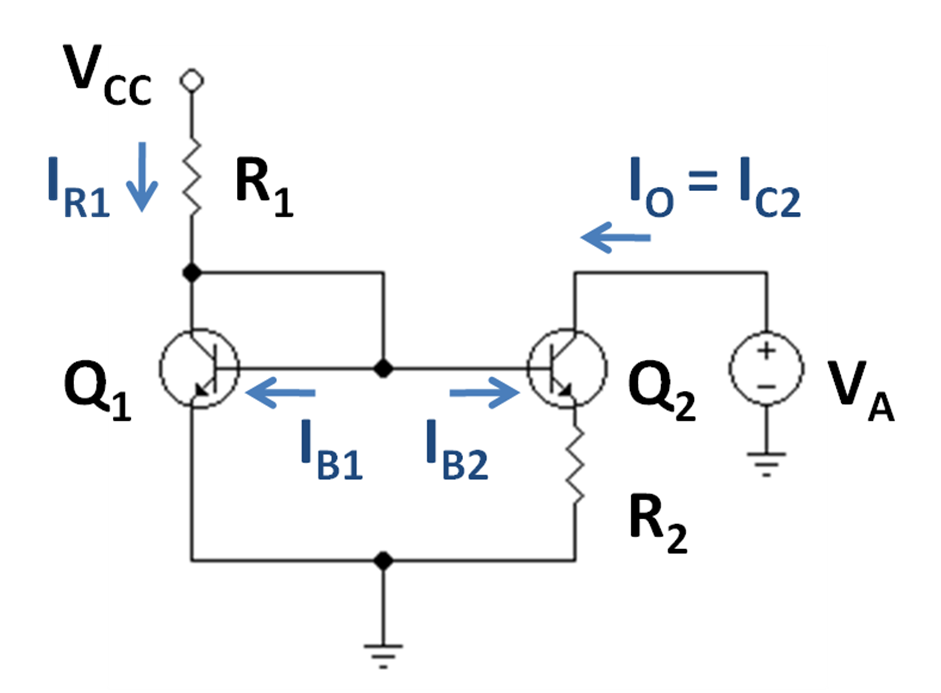

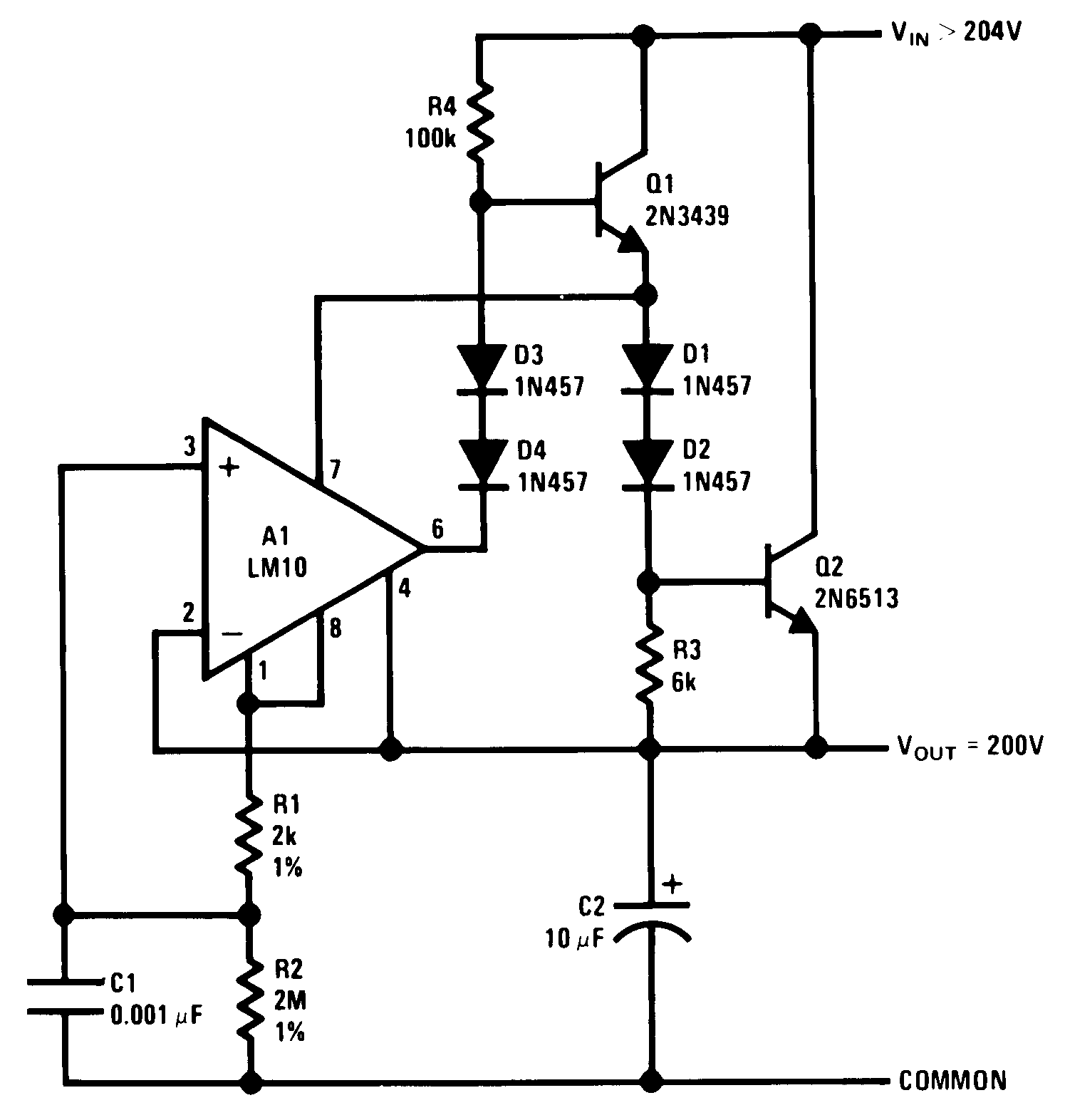

To keep Bob’s legacy alive, we found a modern version of the Hassler Circuit created by Craig and Analog Zoo. Bob’s original schematic was never published for the Hassler, so Craig took it upon himself to recreate it:

You can read all about the detail of the Hassler schematic and see the finished circuit in action at Analog Zoo blog.

A Living Legacy

The passing of Bob Widlar left behind not only a transformed semiconductor industry but also a way of engineering that just isn’t the same today. We often spend our years in EE education learning about Faraday, Ohm, and Ampère, but never really connect with the more recent engineering personalities of our times like Widlar. Bob shows off a truly unique side of engineering that borders on art, and if there’s one thing he was known for, it was that he never designed an obvious circuit.

More importantly, though, Bob’s personality triggers a sort of reminisce about the days of free expression and personality in our workplace. In an age where everything has gone digital and the world functions on 1s and 0s, it might just be that we need more personalities like Bob Widlar to inject life into our modern engineering cultures.

Keep Bob’s spirit alive, design your very own Hassler Circuit in EAGLE! Try Autodesk EAGLE for free today.