George Westinghouse Jr., 1910-1912.

George Westinghouse Jr. Was More Than a Rival

If George Westinghouse Jr. was a candy bar, he’d be a Butterfinger BB—beloved, adaptive, and gone before his time. Like both versions of the Butterfinger, Westinghouse was the kind of guy who really stuck to your teeth, so much so that you’ve probably only heard about Westinghouse the villian, a menace to both Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla. Then again, it is a matter of perspective.

The popular story is the one in which he buys Tesla’s patents and hires him to improve his AC motor. It’s the one where he forms Westinghouse Electric to compete with Edison’s direct current system and begins what becomes known as The Seven Years War after DC power seeks to discredit AC power as a hazard to human life, following its use as the official power source of executions—a grim tale, certainly, but not the full story (and more on that later).

Westinghouse was instead a prolific inventor and humanitarian. At just 19, he received his very first patent for the railway air brake, reforming the power industry. While he may have struggled with teamwork, he was far from the executioner the AC power people might have you believe.

Off the Rails

Born in Central Bridge, New York, Westinghouse used his father’s machine shop to explore his interest in steam engines. During the Civil War, he halted his exploration to serve in the Union army, returning as soon as he was able. While in the army, Westinghouse recognized the importance of the railway in growing the United States. Just like the Butterfinger BB, he had all the makings of a perfect candy—or in his case, an engineer. He just had to take that host of experiences, the crispy filling in his perfect orb shape, and apply those tools to his work.

Finally, In 1869, he invented the air brake, which worked to make rail travel safer.

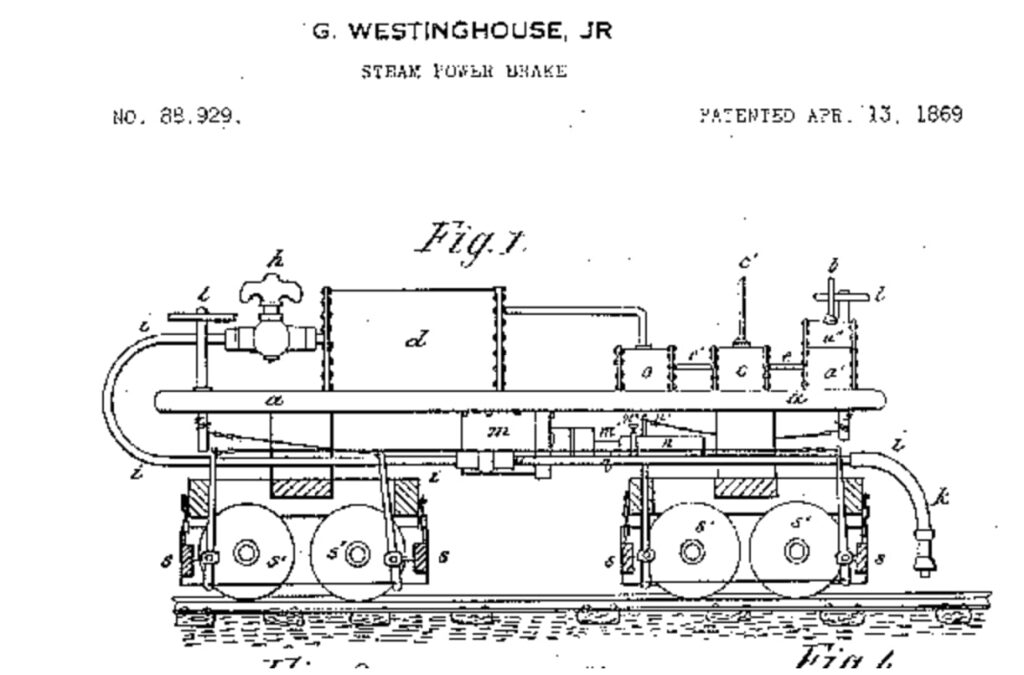

Westinghouse Jr.’s first patented design. [Image source: Edison Tech Center]

The first air brake was an air pump, pressure vessel, and engineer’s valve on the train, with a train pipe and brake cylinder on each train car. Next came the automatic air brake, which involved the invention of the triple valve and an air cylinder for every car.

The plain automatic air brake worked by sustaining air pressure in the auxiliary reservoirs and in the train pipe when the brakes were not applied. When pressure was released in the train pipe, the triple valve on each car would apply the brakes. To release the brakes, the pressure in the train pipe was increased to allow for pressure in each auxiliary cylinder to build, making the triple valve close the inlet to the brake cylinder, opening the inlet to the auxiliary reservoir, and allowing equilibrium.

The quick action triple valve built upon Westinghouse’s previous technology, yet again improving rail travel. The quick action triple valve allowed for faster application of brakes by venting air from the brake pipe to individual cars, causing brakes to work more quickly, which was especially useful in emergencies.

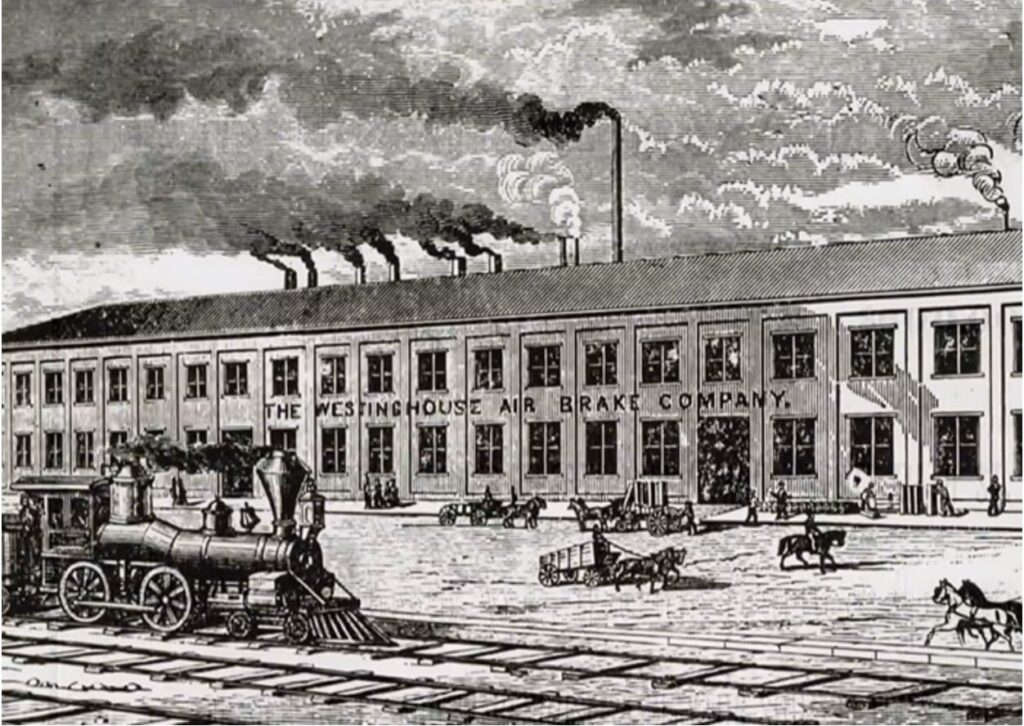

The Westinghouse Air Brake Company, founded in 1869. [Image source: Westinghouse.com]

Westinghouse then began the Westinghouse Air Brake Company, which was but one of over 60 companies he started to market his inventions, as well as the inventions of others. And finally, the 1893 Railroad Safety Appliance Act made air brakes compulsory.

A Face for Radio (and Natural Gas and Electricity)

Of course, Westinghouse was responsible for more than just the air brake. With so pertinent experiences available to him throughout the beginning of his life, he was able to take advantage of those tools and make the most of his time and talents. In fact, in his lifetime, he held more than 300 patents. He’s responsible for gas shock absorbers, too, which offer the smooth ride to which you’ve become so accustomed—this actually developed from early attempts to improve safety on the railway.

Enjoy easy access to natural gas? You can thank Westinghouse for that, too. He had a natural gas well drilled on his property in Philadelphia so that he could refine the reduction valve that provided for natural gas to be safely distributed into homes, giving Pittsburgh the nation’s first large-scale delivery system for natural gas.

It was his work in natural gas that both villainized him and led him to believe that there might be a better way to distribute AC electricity more widely, despite the prevalence of DC electricity. While Edison was pushing DC power, Westinghouse had visions of AC electricity, which could travel to more remote areas. Working with William Stanley Jr., a physicist and engineer, and Tesla, Westinghouse developed a transformer that reduced the current for use in population centers and increased in power for distribution across distances.

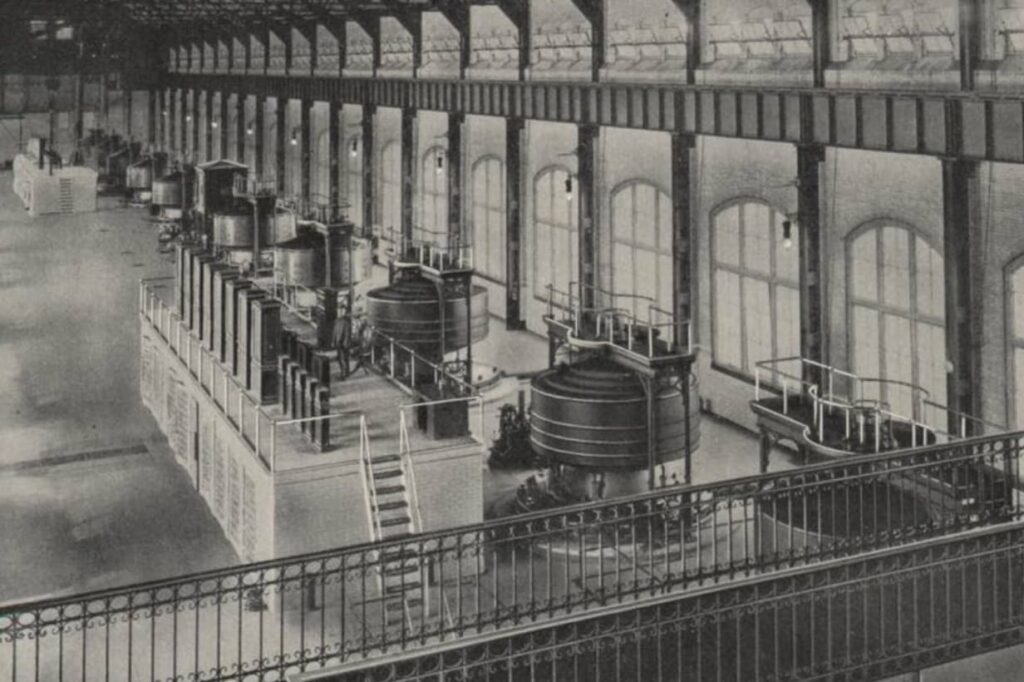

Westinghouse’s hydroelectric generators at Niagra Falls. [Image source: Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company, Wikipedia]

Westinghouse gained the development rights for Niagara Falls and, building upon Tesla’s work, built a hydroelectric power plant at the falls, which supplied power 22 miles away to Buffalo, New York. This was the furthest electricity had ever traveled and the first system of such scale to source energy from one circuit for a variety of industries including railway, lighting, and power.

On top of it all, similar to the chocolate shell that houses each and every unique Butterfinger BB, Westinghouse was also a radio man. He owned the first commercial station and first commercial radio broadcast. In the 1920s, his company was working on television technology alongside their work building huge motors for power industrial sites and ships.

George Westinghouse Jr., Humanitarian

Workers at Westinghouse Air Brake Company. [Image source: www.loc.gov.]

The Westinghouse Air Brake Company was one of many. Westinghouse built facilities east of the city near employee homes, eventually moving his air brake facility from Pittsburgh to Wilmerding, Pennsylvania. Compared to similar companies, the employees at Westinghouse Air Brake company were treated well—9 hour workdays instead of 10 or 12, half holidays on Saturday afternoon. There were employee programs and affordable housing options built by the company. While the air brake was making rail travel safer, Westinghouse was making life better for the people around him.

In 2000, Westinghouse Company finally shut its doors as Pittsburg and the surrounding areas said goodbye to an industrial past. Successors to the company continue to operate today.

Westinghouse’s businesses excelled—until they didn’t. In 1907, he lost control of his companies in a financial panic. By 1911, he’d cut ties completely. Then, his health began to fail. Like the Butterfinger BB, Westinghouse passed into oblivion, his legacy peppered across the landscape.

Westinghouse had all the tools he needed to become a success, and he took advantage of them straight away. Will you do the same? Download Eagle today to get your best shot.