Elevate your design and manufacturing processes with Autodesk Fusion

Jaundice presents a big problem for newborns: Left untreated, this common ailment can lead to brain damage and even death. Sadly, many parts of the world lack the necessary equipment for treatment, so up to 100,000 babies die each year from this highly curable illness.

Neonatologist Donna Brezinski and her team at Boston-based Little Sparrows Technologies are working to change that trend with a low-cost portable phototherapy unit designed to cure jaundice while working within the constraints of health care systems with fewer resources.

A World-Class Standard of Care, Anywhere in the World

Brezinski got involved with this issue when she led the neonatal ICU at a community hospital, where she wanted to procure a second phototherapy device so the facility could treat a pair of jaundiced twins. Although she landed a donation to cover the high cost of the device, she wondered about areas of the world where it wouldn’t work to ask for such a donation.

At the same time, she was serving as a research affiliate at MIT, working to improve medical care while patients were in transit from community hospitals to urban centers by maintaining constant communication with paramedics. The point was “to raise the level of care to meet the needs of the patient, regardless of where the patient is.”

The doctor has pursued that same philosophy ever since she founded Little Sparrows — “to meet or exceed the level of care that patients get in the United States.”

Jaundice Doesn’t Have to Be a Problem

“Jaundice is one of the most preventable causes of neonatal death in the developing world,” Brezinski explains. The condition arises from a buildup of bilirubin, a substance that occurs naturally in all of our bodies. For most people, ordinary liver functions prevent such a buildup, but the livers of newborn infants — especially premature ones — can’t always cope.

A small excess of bilirubin causes yellowing of the skin, which affects about 60% of full-term and 80% of pre-term newborns. In severe cases, the substance acts as a neurotoxin that can cause deafness, vision impairment, cerebral palsy, or death. About 10% of all newborns are at high risk — yet jaundice can be cured in almost all cases by blue-light phototherapy.

In the developing world, babies often receive limited skilled medical care during pregnancy, delivery, and the first week of life. In the U.S., Brezinski explains, screening for jaundice is “part of routine care of the newborn,” but in places like Burundi, where Little Sparrows has a pilot program, screening is often “inadequate or absent, for any number of reasons.”

As the doctor puts it, “Even though we could cure it, we can’t treat it [in those places] — and that is the tragedy.”

Portable, Affordable Treatment for Neonatal Jaundice

Brezinski tackled this challenge by getting her hands dirty. “I actually started by building prototypes at my kitchen table,” she says, working to construct an inexpensive phototherapy device as good or better than traditional ones using nothing but parts she could order online.

Through several generations of design prototypes, she kept in mind not only the clinical requirements for treating neonatal jaundice, but also practical constraints “to be sure this was going to be usable and deployable in a low-resource area.”

“All of your user and context restraints have to inform what your final outcome will be,” she adds. She has developed the device first on her own, then with the help of her physician husband, Gary Gilbert, and ultimately with the broader Little Sparrows team. Throughout that process, Brezinski has kept the unit lightweight and easy to use even for caregivers with limited medical training or in facilities where electricity may be available for only part of the day.

Building a Better Phototherapy Device

Throughout the process, the design team keeps in mind that “the user is the baby,” not the person who turns the machine on.

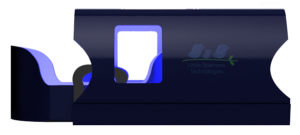

Brezinski and her product engineer, Erica Kontson and biomedical engineer Shreyas Renganathan, are now working with a design that has two components: a “nest” to cradle the baby, and an enclosing light array. Brezinski says that “the Fusion 360 software really lets us see how those two components interact with each other,” and to iterate rapidly through multiple designs between fabrication of physical prototypes.

Brezinski and her product engineer, Erica Kontson and biomedical engineer Shreyas Renganathan, are now working with a design that has two components: a “nest” to cradle the baby, and an enclosing light array. Brezinski says that “the Fusion 360 software really lets us see how those two components interact with each other,” and to iterate rapidly through multiple designs between fabrication of physical prototypes.

Having attended Autodesk University to sharpen her design and CAD modeling skills, Kontson is now using Fusion 360 to refine the therapy unit’s design. The software’s sculpting environment helps with the shape of the enclosure, and the rendering space allows Kontson to simulate LEDs within the model to see exactly where the light falls. She says that they can also simulate stresses and fatigue on the product, which is especially useful because it keeps them from doing that manually “with the few [physical] prototypes we have.”

Bringing a New Medical Device to Market

Brezinski notes that “We know the product works, and we could just make a bunch of these right now.” However, the team continues to learn from it s ongoing field tests in Africa, which will soon expand to a second site in Burundi and a site in Tanzania. As new field data is folded back into the design of the unit, it also informs the company’s market approach.

s ongoing field tests in Africa, which will soon expand to a second site in Burundi and a site in Tanzania. As new field data is folded back into the design of the unit, it also informs the company’s market approach.

The doctor points out the “easy pitfall for a lot of people” to ignore economic realities or market constraints. Even when you want to have a global impact, she says, “You still operate in the real world.”

The transition from the doctor’s kitchen table to the real world started in 2012, when an early prototype of the device was a finalist in the Saving Lives at Birth competition. Realizing that she needed to leverage the business community, Brezinski founded Little Sparrows early in 2013. Since then, she has secured support from the National Institutes of Health and the Autodesk Entrepreneur Impact Program.

Now Kontson is working through the regulatory requirements to gain FDA approval. This will allow the company to sell the device in the United States, which will expand the company’s market presence while meeting a need for phototherapy in rural areas of the country such as Indian reservations. Beyond that, FDA approval will demonstrate that the product does indeed meet the highest standard of care.

A Vision for the Future

“The bar we set is pretty high,” Brezinski says. As Little Sparrows continues to develop its product, the team is exploring how to use it for teaching and instruction. Software again plays a key role: while it’s impossible to instantly deploy thousands of additional physicians to the developing world, it’s quite practical to use CAD modeling to simulate what it’s like to treat an infant in the Little Sparrows device — and to share that through a downloadable repository.

The challenge is huge, but Brezinski’s enthusiasm bubbles over: “We remain optimistic — we think we can do it!”