& Construction

Integrated BIM tools, including Revit, AutoCAD, and Civil 3D

& Manufacturing

Professional CAD/CAM tools built on Inventor and AutoCAD

2 min read

A look at how generative design in Fusion 360 inspires mountain bike company Starling Cycles’ traditional, human-led design process.

Joe McEwan likes to keep things simple. After 20 years as an aerospace engineer, he turned his hobby of building bike frames into a full-time career and thriving startup business: Starling Cycles, a line of mountain bikes made by hand in the UK.

“My goal is to use my engineering background to make bikes that ride well,” he says. “Simple and elegant. Not overcomplicated or adding features for the sake of marketing. That’s the idea.”

Given his traditional approach, McEwan is the last person you might expect to champion generative design. Nevertheless, McEwan’s first experience with the technology has convinced him of its potential to augment the overall design process.

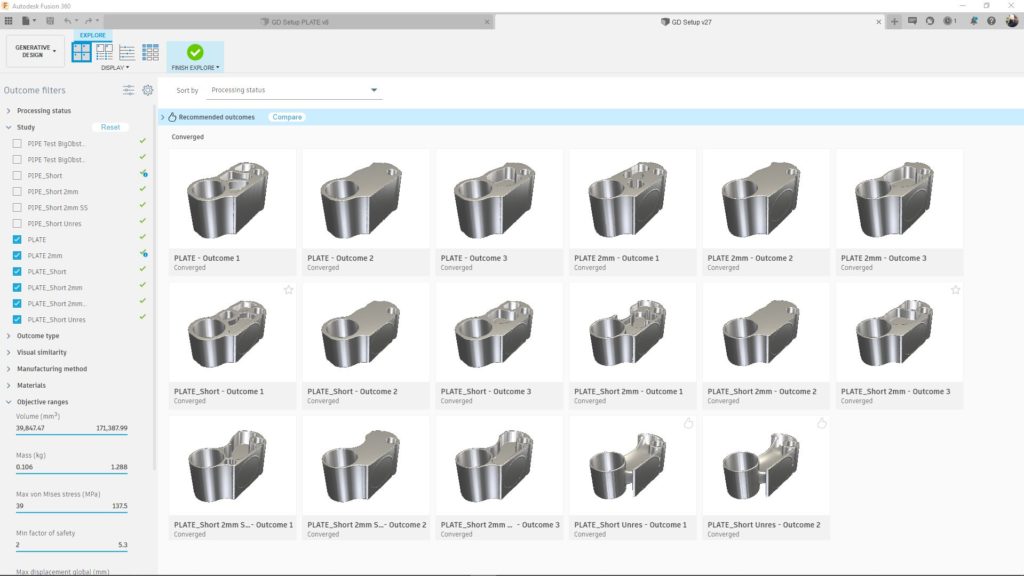

“Generative design is really interesting,” McEwan says. “I’m still learning about where it can work well and what structures it can improve. The assumption is that you put the loads in and get a fancy part out, but it’s much more involved. Selecting the right parts to optimize is challenging.”

McEwan was introduced to generative design by an engineering student from Bristol University. The two had collaborated on a swing arm redesign presented at Autodesk University, then decided to give generative design a try for the main pivot structure of a bike frame.

“I wanted to change the design for easier manufacturing,” McEwan says. “The bearings sit in the main frame in aluminum cups, and there are several processes involved for making the frame and cutting a hole to weld in the housing. There are often alignment issues. It would be much easier to have a machined part that drops right in. Generative design with a 2.5-axis constraint made sense.”

One challenge was the lack of loading data, which can be difficult to generate for a mountain bike because it is so dynamic. McEwan used his engineering experience to provide the initial loads for the frame, and the Autodesk team used simulation to extrapolate the loads for the pivot structure. Then the generative design engine went to work.

“We found one area where we could remove a lot of material, which was really beneficial,” McEwan says. “We ended up using the load path analysis from the generative results to inform my design, so it was really a combination of the two approaches.”

In retrospect, the tight physical limitations of the part — given its central location in the frame — did not give the generative design engine much room to work. Nevertheless, McEwan believes the experiment was valuable.

“Even if you’re uncertain about the loading inputs, you still get ideas from generative design that point you in the right direction,” he says. “Sometimes you stick with a design because that’s how it’s always been done. It’s good to see a different way to solve the same problem and use the generative design output to take a new approach.”

Learn more about how generative design can improve your team’s workflow and possibilities here.

By clicking subscribe, I agree to receive the Fusion newsletter and acknowledge the Autodesk Privacy Statement.

Success!

May we collect and use your data?

Learn more about the Third Party Services we use and our Privacy Statement.May we collect and use your data to tailor your experience?

Explore the benefits of a customized experience by managing your privacy settings for this site or visit our Privacy Statement to learn more about your options.