Tommy Flowers and Colossus: How an Electrical Engineer Saved Lives in WWII

Though he sounds like a famous botanist, Tommy Flowers is among the greatest electrical engineers in history, winning his fame via his work on Colossus, which is not a dinosaur long extinct, but rather the first programmable computer. The work Flowers contributed was anything but ordinary. His work saved thousands of lives during World War II and may have even shortened the war.

Growing Up

Born in December of 1905 in London, Flowers took an apprenticeship in mechanical engineering and eventually attended the University of London, where he got a degree in electrical engineering. By 1926, he was a member of the General Post Office, where he served in telecommunications and then in their research center.

Flowers married in 1935 and had two sons. By 1939, he believed in the possibility of an all-electronic system as World War II began.

The Beginnings of War

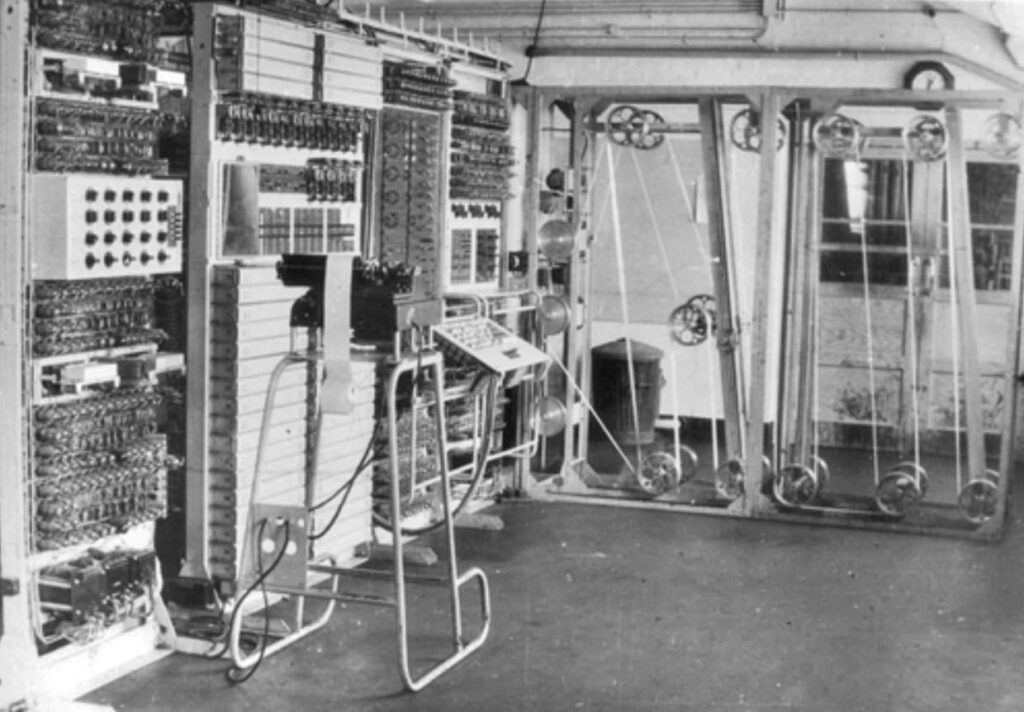

Heath Robinson. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As the GPO research unit relocated, their skills were to be utilized for the war. Alan Turing asked Flowers for help in building a Bombe Machine decoder for decoding German messages. While Flowers failed, he made an impression on Turing, who introduced him to mathematician Max Newman, who had followed William Tutte’s work in decoding. Tuttle was thorough, but his process was slow. They were decoding by hand—and eventually by a simple machine called Heath Robinson.

Flowers was asked to fix Heath Robinson, but he believed himself capable of building a new and better version, which he attempted in February of 1943. He worked until December, which is when Colossus was born.

Colossus Emerges

One of the first programmable computers in the world, Colossus represented a major engineering feat. With approximately 1,800 valves and only one paper tape, people warned that it might be unreliable because of failing valves. But Flowers knew that valve failure was largely the result of machines being turned off and on, and Colossus was designed to run constantly.

Because so many doubted his process, Flowers funded Colossus with his own money and built it in his own time. In 1943, he was made a member of the Order of the British Empire and received full backing from the director of Dollis Hill, which meant his team received priority status to acquire parts for their wartime research. In 11 months, they had a machine—named Colossus because of its size.

The Success of Colossus

Where Heath Robinson read only 1,000 characters a minute (and sometimes less, because of poor reliability), Colossus read 5,000 characters a minute and maintained reliability. Heath Robinson continued to be useful in certain scenarios, eventually morphing into Super Robinson at the hands of Flowers, which ran four tapes and could be used for running known-plaintext attack runs.

Colossus was five times faster than Heath Robinson and was delivered to Bletchley Park in January of 1944. It was in operation by February. Tutte and his team of mathematicians provided algorithms, and Flowers got to work on the second version of the programmable computer, called the Mark II, which utilized roughly 2,400 valves and was functional by June of 1944.

The computer gave Allied Supreme Commanders almost instant access to information broadcast over the Lorenz System without alerting Nazis that there had been a breach. The information acquired helped plan D-Day—and likely saved thousands of lives.

By the War’s End

Prior to D-Day, the computer decoded communications that indicated Hitler thought the D-Day landings would happen at Pays de Calais. Accordingly, he would not move troops to Normandy, which saved lives during the Normandy landings.

At the end of the World War II, there were 10 Colossus machines, eight of which were dismantled immediately. The remaining two were used at GCHQ but were also dismantled between 1959 and 1960, never to be seen again—or at least, not for a while.

And what of Tommy Flowers? He received a sum of money for the machine, which didn’t actually cover what he’d spent to bring it to reality. And still, he divided it up amongst his team. After the war, Flowers remained under the Official Secrets Act, where his work remained hidden from the public, as the “first” computer was announced in 1948.

Wasting no time, he continued to work at the Post Office Research Station and led the way for all-electronic telephone exchanges, in place by 1950. His work received a number of awards and is still protected, at least partially, by the Secrets Act.

In the 1970s, some of what Flowers had done finally earned public recognition, and even his family finally learned about all that he’d contributed to war efforts. Beginning in 1993, a volunteer team rebuilt a functioning Colossus Mark II, which still sits on display at the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park. In 1998, Tommy Flowers died at the age of 92.

When it comes to big ideas, sometimes it seems like they’re nearly impossible. Some engineers, like Flowers, might face opposition and doubt when it comes to their designs. But with enough earnest work, some funding, a good plan, and the right team in place, even the most insurmountable designs can become reality. You can get your plan ready to go with EAGLE. Download it for free today.