Description

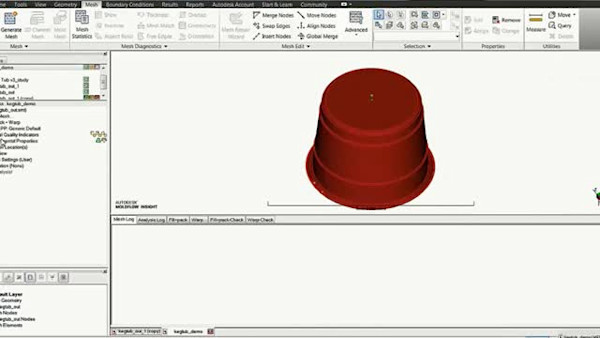

Generative Design in Autodesk Fusion 360 software creates hundreds of innovative optimized design options within a short period of time. However, there is no free lunch. When it comes to engineering, users need to think about the assumptions and limitations of Generative Design. Generative Design models are often slender and do not behave linearly in real life. Material may not be linear elastic over the loading cycle. And the model may need to contact other parts. Event Simulation (Autodesk Fusion 360) and/or Explicit Dynamics analysis (Inventor Nastran) can help confirm the acceptability of the Generative Design model by including all the nonlinear effects that may be encountered during actual use: nonlinear displacement, plasticity, and contact. This session will cover multiple aspects of creating the generative design and performing a simulation with Event Simulation or Explicit Dynamics.

Key Learnings

- Learn how to create a Generative Design model.

- Learn how to identify designs that are potentially better solutions than others.

- Analyze the chosen models with Event Simulation.

- Evaluate the results to identify good features of the design, and potential problems.

Downloads

Tags

Product | |

Industries | |

Topics |

People who like this class also liked

Industry Talk

The When and Why of Generative Design in Fusion 360

Instructional Demo

We’re having a Kegger! Upfront Simulation for Optimized Design.

Instructional Demo